Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > STRESS > Volume 30(4); 2022 > Article

-

Original Article

간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인에 대한 체계적 문헌고찰과 메타분석 -

편보경1,2

, 최희승3

, 최희승3

- Variables Associated with Self-Compassion among Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

-

Bokeung Peun1,2

, Heeseung Choi3

, Heeseung Choi3

-

STRESS 2022;30(4):221-233.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17547/kjsr.2022.30.4.221

Published online: December 30, 2022

1서울대학교 간호대학 박사과정

2분당서울대학교병원 간호사

3서울대학교 간호대학, 간호과학연구소 교수

1Doctoral Student, College of Nursing, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

2Registered Nurse, Bundang Seoul National University Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

3Professor, College of Nursing, The Research Institute of Nursing Science, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- Corresponding author Heeseung Choi College of Nursing, Seoul National University, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea Tel: +82-2-740-8852 Fax: +82-2-740-8852 E-mail: hchoi20@snu.ac.kr

• Received: October 24, 2022 • Revised: December 6, 2022 • Accepted: December 6, 2022

Copyright © 2022 Korean Society of Stress Medicine.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,402 Views

- 107 Download

Key messages

- 본 연구의 목적은 체계적 문헌고찰과 메타분석을 통해 간호사의 자기자비와 관련된 변인을 확인하고 그 효과크기를 평가하는 것이다. Prisma 흐름도를 이용하여 선정된 17편의 논문을 체계적 문헌고찰하고, 이 중 12편의 논문을 메타분석하였다. 간호사의 자기자비(self-compassion)와 관련된 변인은 총 29건이 추출되었다. 긍정 변인 중 자기자비(self-compassion)와 가장 관련이 높은 변인은 삶의 질(quality of life)로 중간 효과크기(effect size=.45)를 보였다. 부정 변인 중 자기자비와 가장 관련이 높은 변인은 소진 (burnout)으로 중간 효과크기(effect size=−.48)를 보였다. 간호사의 자기자비는 간호사의 업무 중 소진 뿐만 아니라 삶의 질과도 밀접한 관련이 있으므로 간호사의 자기자비의 증진은 중요하다.

Abstract

-

Background

- This study aimed to identify variables associated with nurses’ self-compassion and assess their effect sizes through a systematic literature review and meta-analysis.

-

Methods

- Domestic and foreign literature were searched using the Prisma flow diagram; 17 papers were systematically reviewed, and 12 papers underwent meta-analysis.

-

Results

- A total of 29 variables related to nurses’ self-compassion were extracted from the analyzed papers. Furthermore, 12 sub-variables of individual characteristics and 17 sub-variables of job and organizational characteristics were identified. The effect sizes were divided into positive and negative variables to estimate the strength of the relationship between variables related to nurses’ self-compassion. All positive variables showed a small effect size (effect size (ES)= .25). Among the positive variables, quality of life (ES=.45), which had a medium effect size, was most related to self-compassion. Conversely, all negative variables showed a medium effect size (ES=−.35). The negative variable most related to self-compassion was burnout (ES=−.48).

-

Conclusions

- The results suggest that promoting self-compassion is essential as it relates to nurses’ work, mental health, and quality of life. Further studies are needed to verify the mediating effects of self-compassion between stressful events and mental health among nurses. Additionally, it is necessary to develop and apply an intervention related to nurses’ self-compassion that increases the effect of positive variables and decreases the impact of negative variables.

- 간호사는 환자를 돌보는데 있어 환자들의 실질적인 필요를 가장 가까이서 해결하며 의사 및 기타 다른 직업군들과의 소통에서도 중추적인 역할을 담당하고 있다. 이로 인해 간호사는 중증의 업무 스트레스와 소진을 경험할 수 있고, 자신을 돌보는 것에는 소홀해질 수 있다[1]. 간호사가 과도한 스트레스를 경험할 때 만성 피로, 관절질환과 같은 신체 증상과 우울, 불안 등의 심리적인 증상을 겪을 수 있으며, 이는 이직이나 사직을 초래하기도 한다[2]. 특히 최근 몇 년간의 코로나19 팬데믹 상황은 간호사의 업무를 더욱 가중시키고 있으며, 간호사는 예측할 수 없는 업무 상황 속에서 더 큰 신체적, 정신적 어려움을 겪고 있다[3]. 간호사가 적극적으로 자신을 돌보도록 돕는 것은 감정을 관리하는 능력을 향상시키고 소진 및 공감피로와 같은 간호의 부정적인 결과를 예방할 수 있으며 이는 간호사 자신의 웰빙과 다른 사람들에 대한 자비로운 돌봄에도 영향을 준다[4].그러므로 간호사가 스스로 스트레스와 소진, 우울, 불안과 같은 부정적인 심리를 조절하고 긍정적인 정서 상태를 유지하는 것이 중요한데, 이러한 이유에서 최근 자기자비(self-compassion)가 주목받고 있다[5].

- 자기자비(self-compassion)란 다른 사람의 고통에 공감하며 타인의 아픔을 피하지 않고 인식하는 친절함을 스스로에게 행하는 것으로 정의된다[6]. 자기자비를 개념적으로 처음 정의한 학자는 Neff [7]이며, 그는 자기자비가 정반대의 특성을 가진 하위 구성 요소들을 포함하는 3개의 차원으로 이루어져 있다고 보았다. 하위 구성 요소들은 자기친절과 자기판단(self-kindness vs self-judgment), 보편적 인간성과 고립(common humanity vs isolation), 마음챙김과 과잉동일시(mindfullness vs over-identification) 이다. 즉, Neff [7]는 자기자비를 각 차원별로 2개의 하위 구성요소를 가지는 위계적 3차원 구조 또는 위계적 6 요인 구조라고 보았다. 양극단의 하위 요소들은 서로 개념적으로 반대가 되며, 짝을 이루는 두 가지 하위요인은 한 가지 차원만을 측정한다[7,8]. 자기자비의 하위 구성요소를 구체적으로 살펴보면, 자기친절이란 자신에게 가혹한 판단이나 자기비판을 하기보다는 자기 자신을 이해하는 것을 의미한다. 보편적 인간성은 자신의 경험을 자신만 경험하는 고립된 것으로 보기보다는 더 큰 인간 경험의 일부로 보는 것이다. 마음챙김이란 자신의 고통스러운 경험 속에 과도하게 빠지기보다 균형 잡힌 시각으로 보는 것을 말한다[6]. 이러한 구성요소들로 이루어진 자기자비의 수준이 높을수록 스트레스나 우울, 불안 등 심리적 증상들이 감소하므로, 자기자비는 안녕감 증가 및 심리적 건강과 강하게 관련되어 있다고 하였다[9].

- 해외에서 최근 10여 년간 간호사들을 대상으로 한 자기자비 관련 선행연구들을 살펴보면, 간호사들이 인식하는 자기자비는 간호현장에서의 빈번한 감정 조절로 인한 공감피로(compassion fatigue)를 감소시키고[10], 스트레스 경감에 영향을 미친다[11]. 또한 정서지능(emotional intelligence)이 자기자비의 마음챙김, 보편적 인간성, 자기친절의 긍정적 구성요소와 자기판단, 고립감, 과잉동일 시의 부정적 구성요소 모두와 유의미한 상관을 보였다고 보고했다[12]. 반추(rumination) 또한 자기자비의 부정적 구성요소와는 정적 상관관계가, 자기자비 긍정적 구성 요소와는 부적 상관관계가 있다고 하였다[13]. 국내에서 간호사의 자기자비 관련 연구는 아직 부족한 실정이나, 연구들에서 간호사의 자기자비와 관련 변인들의 관계를 다음과 같이 밝혀낸 바 있다. 임상간호사의 업무수행 능력이 분노관리 능력, 회복탄력성, 자기자비와 유의한 정적 상관관계가 있었으며[14], 보훈병원 간호사의 공감피로가 자기자비의 부정적 하위요인인 과잉동일시와 정적 상관관계를 보이고, 공감만족은 자기자비와 정적 상관관계를 보였다[15]. 선행연구들의 고찰을 종합해보면, 자기자비의 긍정적 구성요소는 간호사의 정서지능, 회복탄력성, 업무수행 능력과 같은 변인들과 정적 상관관계가 있고[12,14], 자기자비의 부정적 구성요소는 반추, 공감피로, 소진, 스트레스와 정적 상관관계가 있음을 알 수 있다[5,10,11,13].

- 선행연구들을 통해 간호사의 자기자비와 관련 요인들 간의 상관관계를 살펴보았을 때, 간호사의 자기자비 증진을 통한 삶의 질 증진 및 간호 서비스의 질 제고라는 결과를 기대할 수 있을 것으로 판단된다. 그러나 선행연구들에서는 간호사의 자기자비가 관련 변인과 가지는 정적, 부적 관련성들이 일관성 있게 확인되지 않았으며, 특히 정적, 부적 변인들 중 간호사의 자기자비와 상관이 높은 변인들이 구체적으로 밝혀지지 않아 자기자비를 간호현장에 적용함에 있어 한계가 있다. 이에 본 연구는 간호사의 자기 자비와 관련 변인에 대한 체계적 문헌고찰 및 메타분석을 통해 선행연구의 결과들을 종합하고, 주요 관련 변인과 관련 변인의 정적, 부적 관계 확인하여 그 효과크기를 보아 향후 이를 간호 실무에 적용하는 근거로 삼고자 한다. 구체적인 연구목적은 다음과 같다.

- 첫째, 체계적 문헌고찰을 통해 선별된 연구에서 간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인을 파악한다.

- 둘째, 메타분석을 통해 간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인들의 효과크기를 파악한다.

- 셋째, 메타분석에 포함된 연구의 출판편향을 검증한다.

서 론

- 1. 연구설계

- 본 연구는 간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인을 분석한 체계적 문헌고찰 및 메타분석 연구이다.

- 2. 문헌 검색 전략

- 본 연구의 문헌 선정을 위한 핵심질문 구성요소(PICO)는 간호사(population), 자기자비(intervention), 자기자비 관련 변인(outcomes)으로 설정하였다. 이에 따른 문헌의 선정과 배제기준은 다음과 같다.

- 선정기준은 첫째, 간호사의 자기자비와 관련된 연구 및 자기자비의 긍정적 하위요인인 마음챙김, 자기친절, 보편적 인간성을 다룬 연구, 둘째, 간호사의 자기자비에 대한 설문조사 결과를 분석한 양적연구, 셋째, 한국어와 영어로 출판된 국내외 자기자비 학술 논문, 넷째, 간호사의 자기자비와 관련 변인과의 관계를 효과크기로 변환 가능한 통계치(r, β 등)를 제시한 논문으로 하였다.

- 배제기준은 첫째, 한국어나 영어 외 다른 언어로 출판된 연구, 둘째, 간호사를 제외한 의료종사자(의사, 병원 직원 등), 환자 및 보호자, 간호 대학생을 대상으로 한 연구, 셋째, 질적연구, 고찰연구, 중재연구, 학위논문, grey literature, 넷째, Neff [16]의 self-compassion 도구 개발 이전 논문들로 하여 이를 제외시켰다.

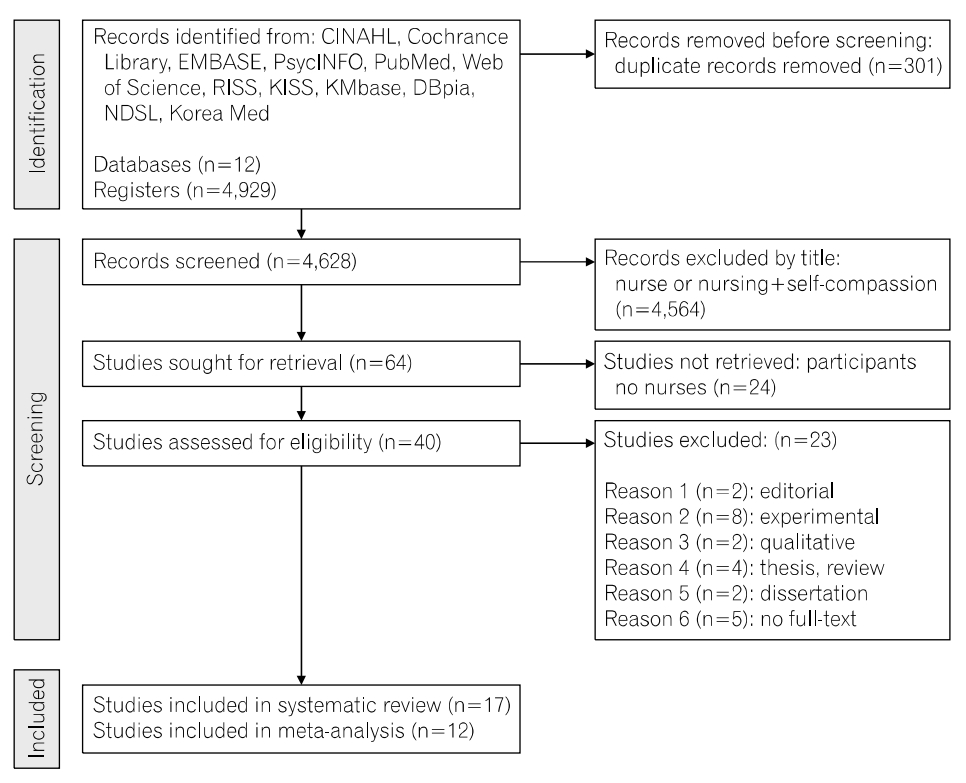

- 문헌검색과 선정의 과정은 PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalysis)의 체계적 문헌고찰 흐름도에 의거하여 수행하였다. 국외 문헌은 Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of science, PsycINFO에서 추출하였으며, 검색어는 ‘nurse’ AND (OR ‘self-compassion*’ OR ‘self-kind*’ OR ‘common human*’OR ‘mindful*’)을 조합하여 검색하였다. 국내 문헌은 RISS, KISS, KMBASE, DBpia, NDSL, KoreaMed에서 ‘간호사’ AND ‘자기자비’ 로 검색한 결과물을 추출하였다. 자료의 추출은 2022년 1월 2일에서 1월 3일까지 검색하였으며. Neff [16]가 self-compassion 도구를 2003년도에 처음 개발하였으므로 그 이후로 출판된 문헌을 검색하였다. 데이터베이스를 통해 검색된 문헌들은 서지 관리 프로그램인 EndNote를 이용하여 반출한 후 중복 자료를 제거하고 정리하였다. 최초 문헌검색은 연구자 1인이 진행했고 검색에 활용된 검색식과 전체 검색된 데이터베이스는 서울대학교 의학도서관 사서를 통해 재검색을 의뢰하여 확인하였다. 이후 문헌 검색 과정과 결과를 연구자 2인이 함께 평가하였다.

- 문헌선정 과정은 국내외 문헌을 검색하여 총 4,929편을 검색하였고 중복 검색된 논문들을 제외하여 4,628편을 확보하였다. 이후 논문의 제목과 초록을 통해 간호사와 자기자비를 포함하고 있지 않은 문헌들은 제외하여 총 64편을 수집하였다. 이중 의사나 조산사와 같은 기타 의료인력이나 간호학생을 함께 포함한 논문들을 제외하고 간호사만을 대상으로 하는 논문과 간호사의 결과 데이터를 단독으로 확인 가능한 논문 총 40편을 확보하였다. 이후 원문을 확보할 수 없는 문헌과 학위논문, 질적연구를 제외하고 분석 가능하다고 판단되는 논문 17편을 수집하였다. 최종적으로 메타분석이 가능한 논문은 통계처리 불가한 5편을 제외하여 총 12편을 확보하였다. 전 과정은 연구자 2인이 독립적으로 수행한 후 의견 일치도를 확인하고 불일치가 있는 경우 검토하여 최종 결정하였으며, 이 과정에서 연구자 간 일치도를 지속적으로 확인하였다(Fig. 1).

- 3. 문헌의 질 평가

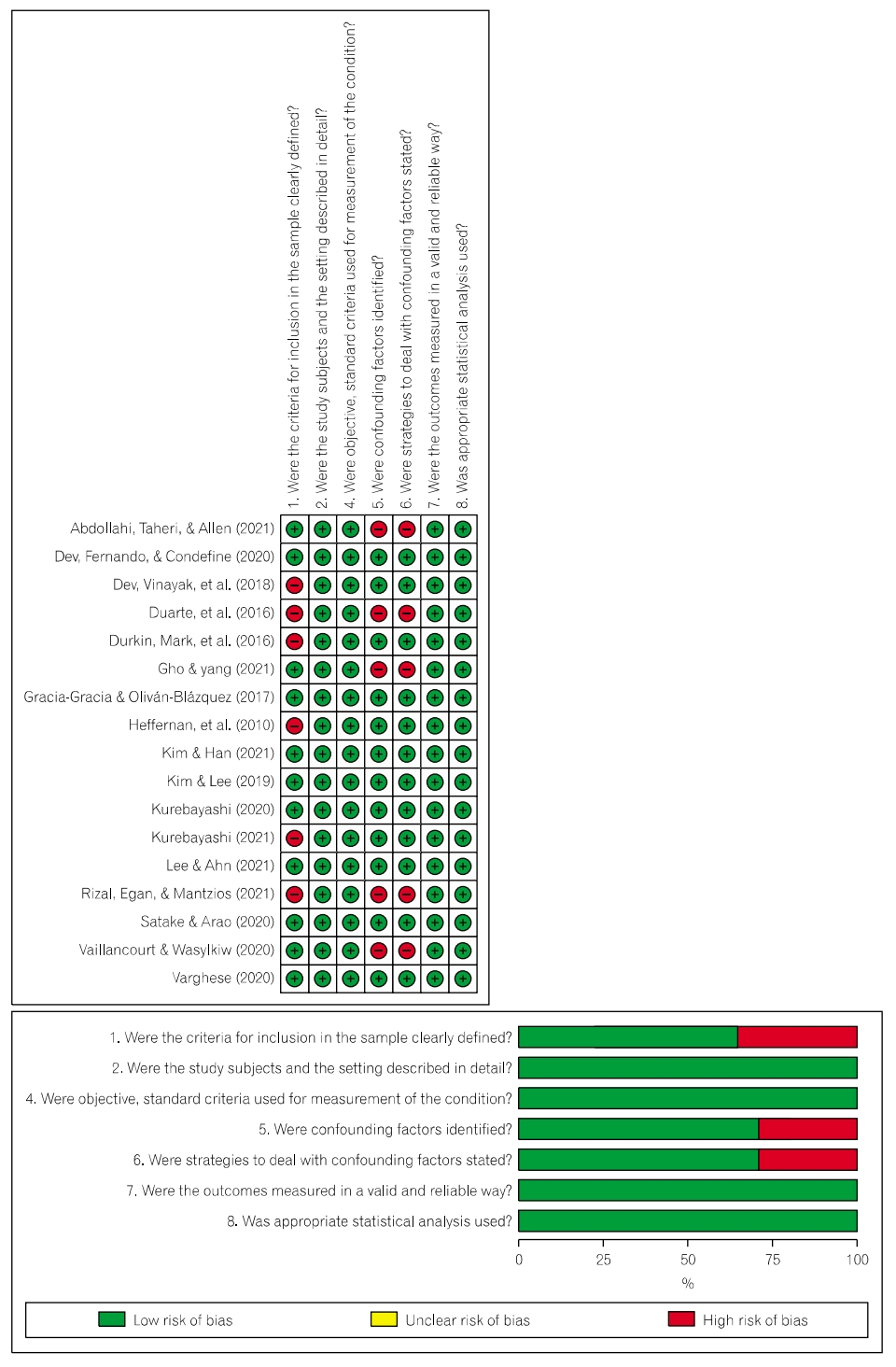

- 간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인을 보고한 연구는 모두 조사연구이므로, 선정된 문헌의 질 평가는 관련성 연구 질 평가 도구인 Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) 체크리스트(Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies) [17]를 활용하였다. JBI 체크리스트는 대상자 선정기준, 대상자 선정기준에 대한 기술, 질병 위험에 대한 노출 여부, 질병의 진단, 혼동변수의 통제, 결과변수 측정, 통계분석 방법의 적절성 등 8개의 항목으로 구성되어 있다. 본 연구에서는 질병 위험에 대한 노출 여부의 항목은 무관하여 제외하고 7개 항목으로 평가하였으며 각 항목에 대하여 ‘예’를 1점, ‘불명확함’, ‘아니오’, ‘해당 없음’을 0점으로 평가하였다[18]. 총점 7점 기준 중간 이상 점수인 4점 이상인 논문은 분석에 포함하였으며, 질 평가 결과 17편이 모두 기준에 부합하는 것으로 나타났다(Fig. 2).

- 4. 자료 분석

- 본 연구의 체계적 문헌 고찰에 포함된 연구 총 17편의 연구 관련 특성을 저자, 연구 출판 연도, 대상자 수, 연구 설계, 관련 변인들, 사용 도구, 질평가 점수, 메타분석 가능여부 별로 나뉘어 분석하였다. 출판 연도별로는 2010년 1편, 2016년 2편, 2017년 1편, 2018년 1편, 2019년 1편, 2020년 5편, 2021년 6편이었다. 연도별로 살펴보았을 때, 간호사와 자기자비 연구는 최근에 더욱 활발하게 연구되고 있는 분야임이 확인된다. 간호사와 연구 설계는 17편 모두 상관관계 연구였으며 대상자 수는 37명에서 801명으로 평균 260명이었다. 연구도구는 16편이 Neff [16]의 Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)을 사용했으며 나머지 1편은 Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Self and Others (SOCS)을 사용했다. 17편 중 5편은 메타분석이 불가한 논문이었으므로 메타분석에 포함한 논문은 12편이었다(Table 1).

- 우선, 메타분석을 위한 자료 코딩을 위해 관련 변인들을 긍정 변인(positive variables), 부정 변인(negative variables)으로 분류하여 코딩지를 만들었다[19-21]. 자기자비와 관련된 변인들은 정적(+) 상관관계와 부적(−) 상관관계를 가진 변인들이 함께 포함되어 있기 때문에, 우선 분석대상 논문의 종속변수와의 상관관계를 확인하였다. 이후 효과크기의 의미가 정적(+)상관 관계인 변인과 부적(−)상관관계인 변인을 각각 긍정 변인과 부정 변인으로 분류하여 분석하였다. 다음으로, 통계처리가 불가하여 메타분석이 불가능한 논문 5편은 분석에서 제외하였다. 아울러 상관계수 사례수가 1개인 경우 메타분석 효과 크기에 기여하지 못한다는 이론에 근거하여 해당 변수들도 분석에서 제거하였다[20,22]. 제거한 변인들은 간호 전문 역량(nurse professional competence), 감독과 교육자(supervison and teacher), 마음챙김(mindfulness), 분노 조절 능력(anger management ability) 수동적 대처(passive coping), 수면(sleep), 업무량(workload), 업무성과(work performance), 임종 간호를 실행 할 수 있는 능력에 대한 확신(confilict about ability to practice end-of-life care), 적극적 대처(active coping), 정서지능(emotional intelligence), 직무만족(job satisfaction), 학습환경(learning environment)과 회복력(resilience)이었다.

- 마지막으로, 유사한 개념으로 판단되는 변인들은 문헌 고찰과 연구자들 간의 논의를 통해 하나의 개념으로 통합하였다. 첫째, 불안 애착과 회피 애착은 불안정 애착(unstable attachment)으로 통합하였다. 불안 애착(anxiety attachment)은 거절당하는 것과 버림받는 것에 대한 두려움 혹은 타인에게 인정받는 것에 대해 과도하게 집착하는 것을 말한다. 또 회피 애착(avoidant attachment)은 의존성과 친밀함에 대해 불편하게 느끼거나 혹은 자기 의존감에 대한 과도한 욕구 등을 의미한다[23]. 둘째, 소진 장애(burnout barriers), 환경 장애(environmental barriers), 환자와 가족 장애(patient and family barriers), 임상 장애(clinical barriers)는 장애들(barriers)로 통합하였다. 소진 장애는 간호사가 제한된 시간 안에 돌보아야 하는 환자가 너무 많은 상황에서 느낄 수 있는 것이며 환경 장애는 전화나 문자와 같이 환자 돌봄에 방해가 될 수 있는 요소들을 말한다. 또 환자와 가족 장애는 환자나 그 가족들이 불만을 제기하거나 고소할 수 있다는 우려와 관련 있는 것이며, 임상 장애는 현재의 치료법이 예상치 못한 부작용을 일으킬 수 있다는 우려와 관련된다, 셋째, 안녕감(wellbeing)과 삶의 질(quality of life)은 삶의 질(quality of life)로 통일하여 분석하였다[24]. 넷째, 스트레스(stress)와 이차적 외상스트레스(secondary traumatic stress)는 스트레스(stress)로 통합하였다.

- 1차 분석대상 자료들은 Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 2.2를 통해 사례 수, 평균 및 표준편차, t-test, F-test, 상관계수(r), p값, 회귀계수(β)를 효과크기(effect size, ES)로 변환 후 분석하였다. 메타분석 과정으로는 우선 개별 효과크기 간 통계적 이질성 존재 여부를 평가하기 위해 Q 통계치와 I2 통계치를 확인한 후, 이질성이 존재하는 경우에는 대상자 수, 자기자비 측정도구, 관련 변인의 특성 같은 조절변인에 따라 효과크기에 차이가 있는지를 분석하였다. 마지막으로 출판 편향(publication bias)을 검증하기 위해서는 먼저 Funnel plot을 통해 시각적으로 평가하고, Egger의 선형 회귀 검정[25]과 Trim-and Fill을 확인하였다.

연구방법

1) 문헌의 선정과 배제기준

(1) 선정기준

(2) 배제기준

2) 문헌검색

1) 선정논문의 일반적 특성 확인

2) 자료 코딩

3) 메타분석 대상 자료의 선정 및 효과크기의 산출

- 1. 간호사 자기자비 관련 변인

- 메타분석 대상 12편의 논문들에서 간호사의 자기자비와 관련된 변인은 총 29건 추출되었다. 간호사의 자기자비간의 정적 상관관계를 가지는 긍정 변인은 10건[5,15,26-30] 부적 상관관계를 가지는 부정 변인은 19건[5,15,23,26-29,31,32]으로 확인되었다. 이 변인들을 조금 더 면밀하게 분석하기 위해 간호사 감정노동과 관련된 변인들을 메타분석한 연구와 국내 간호사의 소진과 관련된 메타분석 연구 등[19,33]에서 개인 특성 변인군, 조직, 직무 특성 변인군으로 나뉘어 분석한 것을 근거로 하여 개인 특성 변인과 직무 및 조직 특성 변인으로 구분하였다. 이를 살펴본 결과, 먼저 개인 특성 변인들은 임상경력(years of clinical experience) 2건, 타인 공감(compassion for others) 2건, 공감만족(compassion satisfaction) 4건, 삶의 질(quality of life) 2건, 불안정 애착(unstable Attachment)이 2건으로, 총 12건이었다. 다음으로 직무 및 조직 특성 변인들은 소진(burnout) 8건, 공감피로(compassion fatigue) 3건, 장애들(barriers) 4건, 스트레스(stress) 2건으로, 총 17건 도출되었다(Table 1, 2).

- 2. 간호사와 자기자비와 관련된 변인들의 효과크기 추정

- 자기자비와 관련된 변인들의 효과크기를 해석하는데 있어 변인들을 긍정 변인(positive variables)과 부정 변인(negative variables)으로 분류하였다. 효과크기의 해석 기준은 .10 이상 .30 미만이면 작은 효과크기, .30 이상 .50 미만이면 중간 효과크기, .50 이상이면 큰 효과크기로 해석하였다[34]. 효과크기의 이질성(heterogeneity) 평가는 Q값의 유의확률이 .10 이하인 동시에 I2값이 75.0% 이상일 경우 동질하지 않다고 판단한다[35]. 이에 따라 동질한 경우에는 고정효과모형(fixed effect model), 동질하지 않은 경우에는 무선효과모형(random effect model)으로 효과크기를 추정하였다(Table 2).

- 긍정 변인 전체의 효과크기는 .25로 작은 효과크기를 보였으며, 통계적으로 유의하였다(95% confidence interval, 95% CI=0.14∼0.36, z=4.31, p<.001). 긍정 변인 중 자기자비와 가장 관련이 높은 변인은 삶의 질(Quality of life, ES=.45)로 중간 효과크기를 보였으며, 통계적으로 유의하였다(95% CI=0.38∼0.51, z=12.86, p<.001). 다음으로 중간 효과크기를 보인 변인은 공감만족(Compassion satisfaction, ES=.35)이었고, 통계적으로 유의하였다(95% CI=0.27∼0.42, z=8.53, p<.001). 임상경력(years of clinical experience, ES=.14)은 작은 효과크기를 보였으며, 마찬가지로 통계적으로 유의하였다(95% CI=0.09∼0.19, z=5.63, p<.001). 반면, 타인 공감(compassion for others, ES=.09)은 효과크기가 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다(95% CI=−0.43∼0.61, z=0.34, p=.732). 즉, 긍정 변인 중 자기자비와 관련이 높은 변인은 삶의 질, 공감 만족, 임상경력 순으로 나타났다.

- 부정 변인 전체의 효과크기는 −.35로 중간 효과크기를 보였으며, 통계적으로 유의하였다(95% CI=−0.43∼−0.27, z=−8.61, p<.001). 부정 변인 중 자기자비와 가장 관련이 높은 변인은 소진(burnout, ES=−.48)으로, 중간 효과 크기를 보였으며, 통계적으로 유의하였다(95% CI=−0.58∼−0.39, z=−9.89, p<.001). 다음으로 작은 효과크기를 보인 변인은 공감피로(Compassion fatigue, ES=−.24, 95% CI=−0.33∼−0.15, z=−5.13, p<.001)와 장애들(barriers, ES=−.22, 95% CI=−0.25∼−0.18, z=−12.37, p<.001)이었으며, 모두 통계적으로 유의하였다. 반면, 불안정 애착(unstable attachment, ES=−.43, 95% CI=−0.87∼0.01, z=−1.92, p=.054)과 스트레스(stress, ES=−.32, 95% CI=−0.95∼0.32, z=−0.98, p=.326)의 경우 효과크기가 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다. 즉, 부정 변인 중 자기자비와 관련이 높은 변인은 소진, 공감피로, 장애들 순으로 나타났다.

- 3. 출판편향에 대한 검정

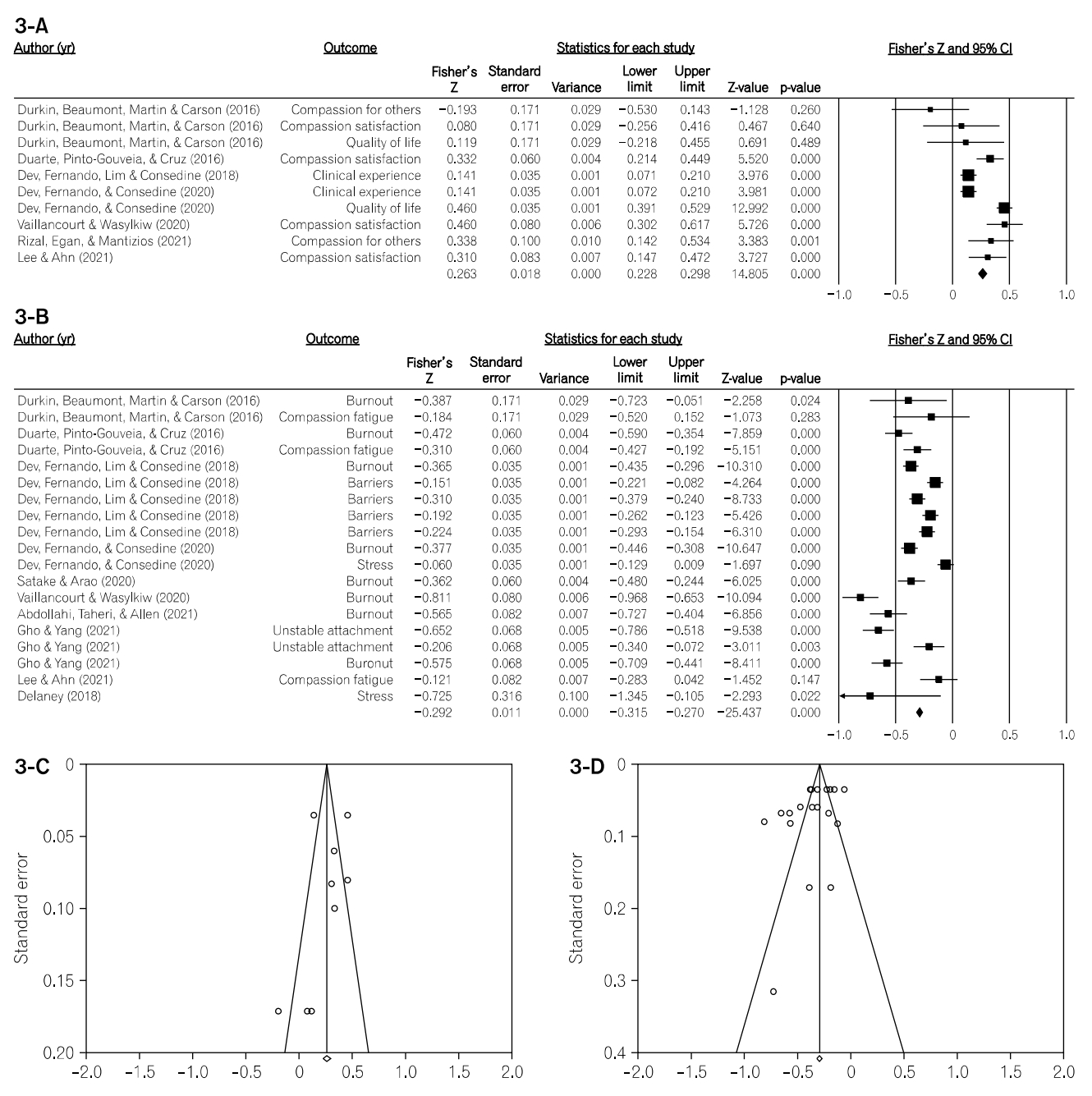

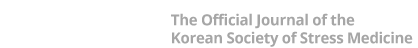

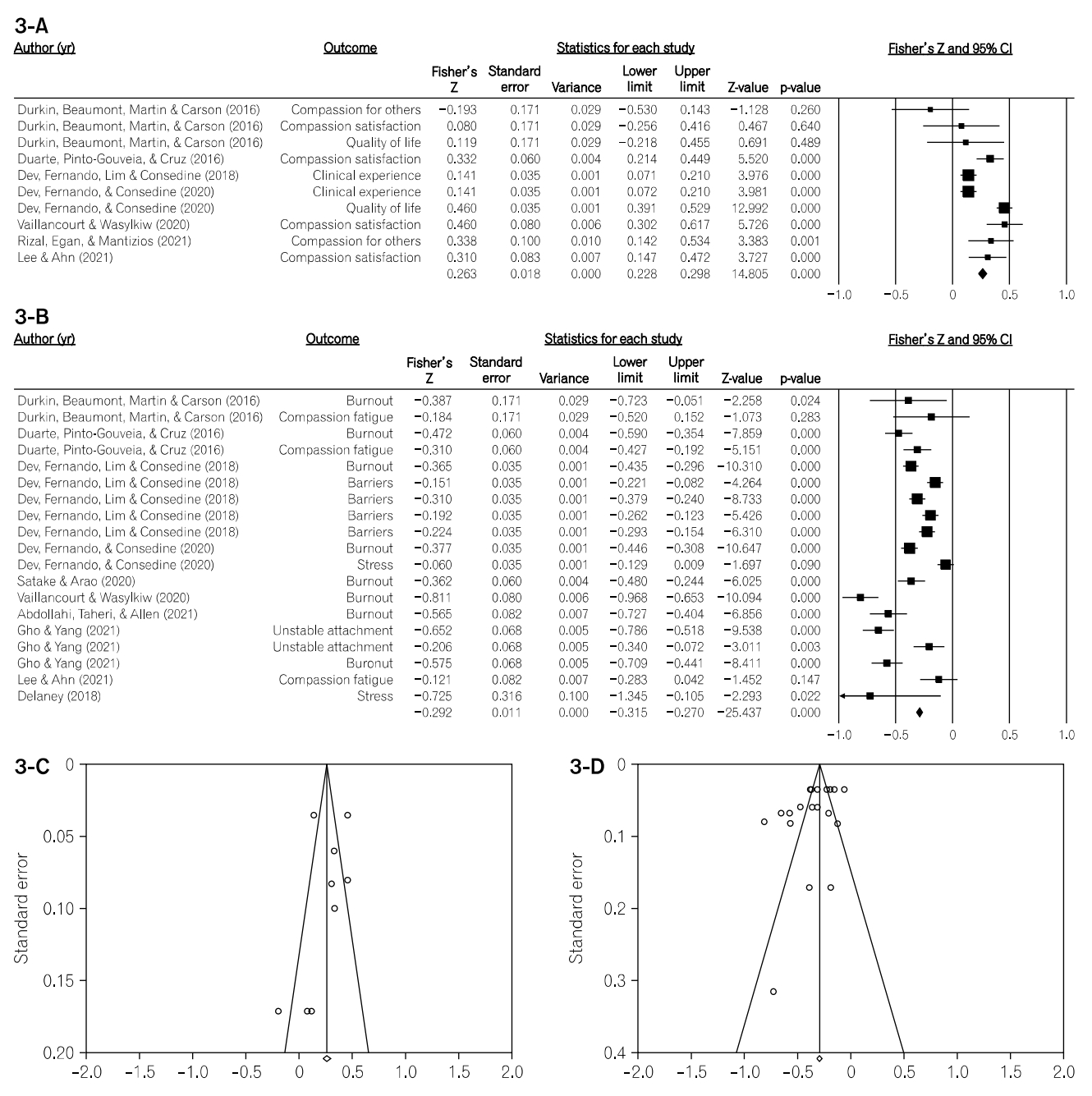

- 출판편향에 대한 결과는 다음과 같다(Fig. 3).

- 긍정 변인들을 Egger’s 회귀분석한 결과 t=0.020, p=.844로 출판편향이 없는 것으로 나타났다. 출판편향이 없으므로 Trim & fill은 보정할 필요가 없었다. 안정성계수(Fail-safe N)는 393개로 안정성 계수 평가기준인 60개(5N+10)보다 컸다. 그러므로 종합적으로 고려했을 때, 출판편향이 발생하지 않은 것으로 판단되었다.

- 부정 변인의 출판편향을 검정한 결과 Egger’s 회귀분석이 t=1.95, p=.068로 나타나 출판편향이 없는 것으로 확인되었다. 출판편향이 없으므로 Trim & fill은 보정할 필요가 없었다. 아울러 안정성계수(Fail-safe N)가 3,213개로 안정성 계수 평가기준인 95개(5N+10)보다 큰 것으로 나타나 종합적으로 고려했을 때, 출판편향이 발생하지 않은 것으로 판단되었다.

결 과

1) 긍정 변인(positive variables)효과크기

2) 부정 변인(negative variables)효과크기

1) 긍정 변인(positive variables)의 출판편향 검정

2) 부정 변인(negative variables)의 출판편향 검정

- 본 연구는 체계적 문헌고찰과 메타분석 방법을 활용하여 간호사의 자기자비에 관한 연구를 분석함으로써 자기자비와 관련된 변인들을 파악하고, 이들 변수들의 상관관계 효과크기를 도출하고자 하였다. 체계적 문헌고찰을 통하여 선정된 문헌에서 메타분석 가능한 12편을 분석하였으며, 연구 목적을 위해 간호사의 자기자비와 관련된 변인들을 추출하였고, 자기자비와 정적 상관이 있는 긍정 변인군과 부적 상관이 있는 부정 변인군으로 나누어 그 효과크기를 알아보았다.

- 첫째, 간호사의 자기자비와 관련된 변인을 파악한 결과, 메타분석 대상 논문에서 총 29건의 변인이 추출되었다. 간호사의 자기자비와 정적 상관관계를 가지는 긍정 변인은 10건[5,15,26-30], 부적 상관관계를 가지는 부정 변인은 19건[5,15,23,26-29,31,32]으로 확인되었다. 이러한 결과는 간호사의 자기자비 관련 요인에서 부정 변인과 관련한 연구가 긍정 변인 관련 연구에 비해서 상대적으로 더 많이 이루어지고 있다는 것을 알 수 있다. 그러므로 향후 간호사 자기자비의 긍정 변인과 관련된 연구가 더욱 필요할 것으로 사료된다.

- 둘째, 간호사 자기자비 관련 효과 크기를 분석함에 있어 개인 특성 변인군과 직무 및 조직 특성 변인군으로 나누어 본 결과 개인 특성 변인군은 12건[5,15,23,26-30], 직무 및 조직 특성 변인군은 17건[5,15,23,26-29,31,32]으로 각각 추출되었다. 특히, 긍정 변인군에는 개인 특성 관련 변인들만 포함되어 있었던 반면, 부정 변인군에는 개인, 직무 및 조직 특성 관련 변인들이 모두 포함되어 있었다. 이는 간호사의 자기자비와 정적인 상관관계에 있는 긍정 변인에 관한 연구가 개인 특성에 관한 연구들에 국한되어 있으며, 직무 및 조직 특성과 관련해서는 충분히 이루어지지 않았음을 보여준다. 그러므로 직무 및 조직 특성에서 간호사 자기자비와 관련한 긍정 변인들에 대한 연구가 추가적으로 필요하다.

- 셋째, 간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인의 효과크기에 있어서 긍정 변인의 전체 효과 크기는 작은 효과 크기로 나타났고, 부정 변인의 전체 효과 크기는 중간 효과 크기로 나타났다. 이러한 연구결과는 간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인들이 긍정 변인보다는 소진[5,23,26-29,31,32], 공감피로[15,26,27] 등의 부정 변인과 더 유의미하고 높은 관련이 있음을 확인할 수 있었다.

- 넷째, 간호사의 자기자비 관련 변인 중에서 긍정 변인들은 삶의 질, 공감만족, 임상경력 순으로 높은 효과크기를 보였다. 본 연구의 결과에서 삶의 질은 긍정 변인들 중에서 첫 번째로 효과크기가 컸고, 이는 자기자비와 삶의 질 간에는 높은 상관이 있다는 선행연구의 결과를 지지한다[36]. 또한, 자기자비 수준이 높을수록 간호사의 삶의 질이 높아진다는 것을 예측할 수 있으나, 아직까지 국내 간호현장에서는 간호사의 삶의 질 증진과 관련하여 자기자비에 대한 관심은 매우 부족한 실정이므로 향후 더욱 관심을 가지고 더 많은 연구가 이루어져야 할 것이다. 한편, 스페인 공공보건의료 분야에 종사하는 간호사를 대상으로 자기돌봄과 자기자비가 간호사의 직업적 삶의 질에 미치는 영향을 살펴본 선행연구[37]에서 자기돌봄과 자기자비가 간호사의 직업적 삶의 질을 예측한다는 결과를 밝힌 바 있는데, 국내에서도 다양한 임상환경에서 일하는 간호사들의 자기자비가 삶의 질과 실제로 어떠한 상관이 있는지를 밝히는 연구들이 더욱 필요할 것으로 사료된다. 다음으로 자기자비와 관련이 높은 변인으로는 공감만족이 확인되었는데, 이러한 결과는 공감만족과 자기자비 간의 상관(r=.89)이 매우 높다는 것을 밝혀낸 연구결과[29]를 지지한다. 공감만족이란 남을 돕는 즐거움이며, 자신이 남을 도울 수 있는 능력을 가지고 있다는 것에서 기인하는 즐거운 감정이다. 따라서, 공감만족은 간호사의 정신적 안녕을 유지시키는 역할을 하고, 업무를 지속할 수 있는 힘을 주어 전문직으로서의 삶의 질을 높인다[38]. 그러므로 간호 현장에서의 공감만족을 자기자비와 더불어 중요한 변인으로 다루는 것이 필요하며, 간호사가 간호 현장에서 남을 돕는 일에 대한 가치를 높이고 스스로도 만족감을 가져 타인과 스스로에 대한 자긍심을 높이는 것이 필수적이다. 본 논의를 바탕으로 간호사의 공감만족이 자기자비와 밀접한 관련이 있음을 고려하여 간호사의 자기자비를 높이는 것이 중요하다. 한편, Delaney는 Neff가 자기자비를 증진시키기 위해 개발한 ‘마음챙김-자기자비 훈련(mindful self-compassion training, MSC)’프로그램을 13명의 간호사에게 8주간 파일럿으로 실시한 연구[39]에서 자기자비와 부적 상관이 있는 소진과 스트레스 줄이고 정적 상관의 회복력과 공감만족을 증진시켰다는 결과를 밝힌 바 있다. 그리고, 소아과 간호사를 대상으로 한 원데이 자기자비 프로그램(one-day self-compassion training program)의 연구[3]에서 22명의 중재군 간호사들의 자기자비, 마음챙김, 공감만족이 괄목할 만한 증진이 보였다고 보고된 바 있어 이러한 프로그램을 국내 상황에 맞게 적용해 볼 수 있을 것으로 사료된다.

- 임상경력 역시 자기자비와 상관이 있는 변인으로 밝혀졌는데, 이는 직위가 높고, 총 근무경력이 많을수록 자기자비가 높게 나타난 연구결과와 일치한다[14]. 간호업무 수행에 있어 임상경력이 높은 간호사는 다양한 경험을 통해 지식과 기술을 습득하면서 간호업무수행 능력을 발전시킬 수 있다[40]. 또한, 복잡한 간호 문제들을 해결하고, 자신감과 성취감을 높여 자신을 명확하게 바라볼 수 있는 정서적 안정감을 통해 긍정적인 자기개념인 자기자비가 향상된 것으로 볼 수 있다[14,41]. 반면, 임상경험이 적은 신규 간호사들은 상대적으로 간호 조직 내에서 부정심리를 더 많이 경험할 수 있으므로, 간호사들에게 특화된 자기자비 중재프로그램이나 교육을 통해 자기자비를 증진할 수 있도록 돕는다면 이들이 임상 현장에 더욱 안정적으로 적응할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다. 이와 관련해 18세 이상의 미국 병원 간호사들을 대상으로 자기자비, 회복탄력성, 통찰력, 임파워먼트 등을 증진시키기 위해 8주간의 심리교육 프로그램을 시행한 연구[42]에서 중재군의 자기자비 및 회복탄력성, 스트레스 인지 수준이 증가되었다는 보고가 있어 국내 상황에 맞게 적용해 볼 수 있을 것으로 보인다.

- 다섯째, 부정 변인들 중 자기자비와 관련이 높은 변인은 소진, 공감피로, 장애들 순이었다. 먼저 부정 변인 중 가장 관련이 높은 변인은 소진이었는데, 이는 소진과 자기자비 간의 부적 상관(r=−.67)을 밝혀낸 결과와 같은 맥락이다[29]. 간호사는 환자의 생명을 다루는 중차대한 일을 담당하고 있으므로 업무의 긴장도가 높고, 정해진 시간 내에 주어진 간호업무를 집중적으로 수행해내야 하는 현장적 특성으로 조직의 위계가 엄격하다. 더욱이, 작은 실수들이 큰 사고로 이어질 수 있어 쉽게 스스로 자책하는 등의 문제가 발생할 수 있다. 아울러 다른 의료진 및 관련 부서 직원들과 소통 및 상호작용을 통해 간호업무를 수행한다는 점에서 장시간 동안 높은 수준의 소진을 경험할 수 있다. 이 때문에 간호사는 스스로 자신을 돌보거나 존중하는 자기자비에는 소홀해질 수밖에 없다[43]. 그러므로 간호사가 자기자비를 증진시키기 위해서는 간호사가 소진을 개인 및 조직 차원에서 적절히 해소하도록 하여 결과적으로 간호서비스의 질을 제고하는 방안이 마련되어야 한다[44]. 이와 관련해 자기자비의 하위요인이 병원간호사 소진에 미치는 영향을 규명한 연구[45]에서 자기자비를 높이면 간호사 소진을 예방할 수 있으므로, 개인차원에서 간호사가 자기자비를 향상시키기 위해 심호흡, 명상, 요가, 아로마 흡입 훈련 등을 적용하고, 병원 및 관리자 차원에서 고립을 예방하는 멘토링 프로그램, 그룹 요가 또는 명상 중재와 같은 프로그램을 정책적으로 지원할 필요가 있음을 제언한 바 있다. 따라서, 이를 고려하여 국내 간호현장에서 개인이나 조직 차원에서의 간호사 자기자비 증진 프로그램들을 적극 마련하는 것이 필요하다.

- 다음으로 공감피로는 자기자비와 부적 상관이 있으며, 이러한 결과는 공감피로와 자기자비 사이의 부적 상관관계(r=−.35)를 확인한 것과 일치한다[46]. 간호사는 업무의 특성상 의료 전문가로서 일상에서 다양한 부상과 고통을 겪는 환자들을 만나며, 이 과정에서 다른 사람의 고통에 민감하게 반응하고 공감해야 하는 피로를 경험한다. 따라서, 공감피로는 간호사에게 여러 부정적인 영향을 줄 수 있으며[47], 자기 스스로를 돌볼 시간이 부족하다는 관점에서 스스로를 존중하고 돌아볼 여유가 없게 만든다[26]. 이와 관련해 급성기 병원에서 근무하는 간호사 180명을 대상으로 자기자비가 공감피로에 대한 대처기전으로 사용될 수 있는지의 여부를 탐색한 연구[48]에서 자기자비가 공감피로에 대한 조절효과와 공감피로를 예측 할 수 있는 능력을 가질 수 있게 함이 확인된 바 있다. 아울러 자기자비를 높이기 위한 간호사 고용 기관의 전략 또한 중요함을 강조하면서 정기적으로 서로의 유사한 경험을 나누는 장을 마련하거나 마음챙김 기반 스트레스 감소 프로그램(mindfulness-based stress reduction, MBSR)과 같은 대상 지원 프로그램의 구현을 제언하고 있어 국내에서도 적용해 볼 수 있을 것이다. 마지막으로, 소진 장애(burnout barriers), 환경 장애(environmental barriers), 환자와 가족 장애(patient and family barriers), 임상 장애(clinical barriers)를 통합한 장애들 또한 자기자비와 부적 상관이 있었다. 이러한 결과는 스스로에 대한 자비는 아니더라도 간호사가 의료현장에서 돌봄대상자들에 대해 자비와 연민을 가지는데 있어 작업 환경 관련 장애가 높은 영향을 준다는 것을 보고한 연구와 맥락이 일치한다[49]. 즉, 간호사가 의료현장에서 직면하는 구조적 장벽과 제한을 완화해야 할 필요성을 강조하고 있는데 본 연구의 결과와 더불어 장애들은 간호사가 의료현장에서 온전한 간호를 수행하는데 있어 어려움이 될 뿐만 아니라 자기자비에도 부정적인 영향을 주므로, 간호사가 자기자비를 증진시키기 위해서는 실질적인 의료 환경의 조정과 정비 또한 필수적임을 보여준다.

- 이상의 논의를 통해 살펴본 결과를 토대로 본 연구의 시사점은 다음과 같다. 우선 자기자비가 간호사의 삶의 질, 공감만족, 임상경력과 긍정적인 상관이 있었고, 소진, 공감피로, 장애들과 부정적인 상관이 있음을 확인하였다. 이러한 연구결과는 간호사가 개인의 정신건강 및 삶의 질을 향상시키고, 간호업무 중 소진과 공감피로와 같은 부정적인 감정들을 적절히 해소하며 진정한 공감만족을 느끼면서 질 높은 간호를 수행하도록 하기 위해서는 자기자비를 증진시킬 수 있는 방안을 마련하는 것이 매우 중요함을 시사한다. 즉, 앞에서 논의한 바와 같이 이미 해외에서는 간호사의 자비자비를 주요하게 다루어 연구를 활발하게 진행하고 있으며, 자기자비 증진 프로그램 및 교육 시행과 더불어 현장 실무에서의 제도 개선의 노력을 이어나가고 있다[3,37,39,42,48]. 그러므로 앞선 선행연구들 및 본 연구의 결과를 바탕으로 국내에서도 자기자비 관련 연구 및 교육, 프로그램 개발, 현장 실무의 제도개선을 통해 간호사의 자기자비를 증진하려는 시도가 절실하다.

- 다음으로 본 연구의 한계점은 다음과 같다. 첫째, 변인의 횟수가 1회인 변인은 메타분석에 기여하지 못하므로 본 연구에서는 일부 유사 변인명을 통합하여 분석한 것이다. 유사 의미를 가진 변인들을 통합하여 분석한 선행연구를 참고하고 변인명은 더 큰 범주로 통합하였으나 변인명을 통합하지 않은 경우 해당 변인이 메타분석에서 제외될 수 있어 결과에서 차이가 발생할 수 있다는 한계를 지닌다. 둘째, 자기자비와 관련 변인들을 면밀하게 분석하기 위해 개인, 직무 및 조직관련 특성으로 분류하였고 분류의 기준은 기존 선행연구들을 참고하였으나 선행연구들에서의 분류 기준 또한 통일되지 않은 점이 있어 긍정 변인군이 개인 변인군으로만 이루어져 있다고 해석하는 것은 관련 변인을 조직이나 직무 변인으로 본다면 해석에 차이가 발생할 수 있다는 한계를 지닌다.

- 이상의 결과를 토대로 추후 연구를 위해 다음과 같이 제언한다. 첫째, 문헌을 통해 간호사의 자기자비와 가장 관련이 있는 긍정 변인과 부정 변인을 살펴보았으므로 이를 통해 실제 간호현장에서 간호사의 자기자비 조절효과나 매개효과를 검증하는 후속연구가 필요하다. 둘째, 간호사 자기자비와 관련이 있는 긍정 변인의 효과는 증가시키고 부정 변인의 효과는 감소시키기 위한 중재를 국내 상황에 맞게 개발하고 이를 적용하는 것이 필요하다. 셋째, 본 연구를 통해 직무나 조직 특성과 관련한 간호사의 자기자비 관련 긍정 변인들에 대해서는 기존 연구가 부족하다는 것을 알 수 있었으므로 이를 위한 후속 연구가 더욱 필요할 것으로 사료된다.

고 찰

Acknowledgments

Fig. 3.Forest plot and funnel plot of positive and negative variables. 3-A. Forest plot of positive variables. 3-B. Forest plot of negative variables. 3-C. Funnel plot of positive variables. 3-D. Funnel plot of negative variables.

Table 1.General characteristics of reviewed studies

Table 2.Effects sizes of variables related to self-compassion in nurses

- 1. Lee JY, Lee MJ, Pak SY. The impact of psychosocial health and self-nurturance on graduate nurse experience. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. 2015;21(5):459-468. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2015.21.5.459Article

- 2. Gracia-Gracia P, Olivάn-Blάzquez B. Burnout and mindfulness self-compassion in nurses of intensive care units: Cross-sectional study. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2017;31(4):225-233. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000215ArticlePubMed

- 3. Franco PL, Christie LM. Effectiveness of a one day self-compassion training for pediatric nurses’ resilience. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2021;61:109-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2021.03.020ArticlePubMed

- 4. Andrews H, Tierney S, Seers K. Needing permission: The experience of self-care and self-compassion in nursing: A constructivist grounded theory study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;101:103436https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103436ArticlePubMed

- 5. Dev V, Fernando AT III, Lim AG, Consedine NS. Does self-compassion mitigate the relationship between burnout and barriers to compassion? A cross-sectional quantitative study of 799 nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2018;81:81-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.02.003ArticlePubMed

- 6. Ko EJ. Analysis on the emotional effect of self-compassion and self-esteem in the occurence of negative life events [dissertation]. Seoul: Korea University; 2014.

- 7. Neff K. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003;2(2):85-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032Article

- 8. Park WR, Hong SH. Self-compassion: A review. The Korean Journal of Elementary Counseling. 2020;19(3):239-280. https://doi.org/10.28972/kjec.2020.19.3.239Article

- 9. Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(1):139-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004Article

- 10. Harwood L, Wilson B, Crandall J, Morano C. Resilience, mindfulness, and self-compassion: Tools for nephrology nurses. Nephrology Nursing Journal. 2021;48(3):241-249. https://doi.org/10.37526/1526-744X.2021.48.3.241ArticlePubMed

- 11. Bluth K, Lathren C, Silbersack Hickey JV, Zimmerman S, Wretman CJ, Sloane PD. Self‐compassion training for certified nurse assistants in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021;69(7):1896-1905. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17155ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Heffernan M, Quinn Griffin MT, McNulty SR, Fitzpatrick JJ. Self‐compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2010;16(4):366-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01853.xArticlePubMed

- 13. Kurebayashi Y. Effects of self‐compassion and self‐focus on sleep disturbances among psychiatric nurses. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2020;56(2):474-480. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12458ArticlePubMed

- 14. Kim Y, Han KS. Work performance, anger management ability, resiliece, and self compassion of clinical nurses. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2021;30(2):110-118. https://doi.org/10.12934/jkpmhn.2021.30.2.110Article

- 15. Lee BR, Ahn SH. Impact of self-compassion, active coping, and passive coping on compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction of nurses at veterans’ hospitals. Global Health and Nursing. 2021;11(2):112-122. https://doi.org/10.35144/ghn.2021.11.2.112Article

- 16. Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2(3):223-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027Article

- 17. Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for analytical cross sectional studies. Adelaide, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

- 18. Chae YR, Lee SH, Jo YM, Kang HY. Factors related to family support for hemodialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2019;31(2):123-135. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2019.31.2.123Article

- 19. Kim SH, Ham YS. A meta-analysis of the variables related to the emotional labor of nurses. Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. 2015;21(3):263-276. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2015.21.3.263Article

- 20. Lee BY, Jung HM. Factors related to positive psychological capital among Korean clinical nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research. 2019;25(3):221-236. https://doi.org/10.22650/JKCNR.2019.25.3.221Article

- 21. Kwon HK, Kim SH, Park SH. A meta-analysis of the correlates of resilience in Korean nurses. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research. 2017;23(1):100-109. https://doi.org/10.22650/JKCNR.2017.23.1.100Article

- 22. Oh SS. Meta-analysis: Theory and practice. Seoul: Konkuk University Press; 2002.

- 23. Gho SY, Yang HC. The effects of adult attachment on burnout among nurses: Focused on the mediation effects of self-compassion. The Journal of Welfare and Counselling Education. 2021;10:73-96.Article

- 24. Kim BY, Lee CS. A meta-analysis of variables related to suicidal ideation in adolescents. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2009;39(5):651-661.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7109):629-634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses’ empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2016;60:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015ArticlePubMed

- 27. Durkin M, Beaumont E, Martin CJH, Carson J. A pilot study exploring the relationship between self-compassion, self-judgement, self-kindness, compassion, professional quality of life and wellbeing among UK community nurses. Nurse Education Today. 2016;46:109-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.030ArticlePubMed

- 28. Dev V, Fernando AT, Consedine NS. Self-compassion as a stress moderator: A cross-sectional study of 1700 doctors, nurses, and medical students. Mindfulness. 2020;11(5):1170-1181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01325-6ArticlePubMedPMC

- 29. Vaillancourt ES, Wasylkiw L. The intermediary role of burnout in the relationship between self-compassion and job satisfaction among nurses. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2020;52(4):246-254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0844562119846274Article

- 30. Rizal F, Egan H, Mantzios M. Mindfulness, compassion, and self-compassion as moderator of environmental support on competency in mental health nursing. SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine. 2021;3(7):1534-1543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00904-5ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Satake Y, Arao H. Self-compassion mediates the association between conflict about ability to practice end-of-life care and burnout in emergency nurses. International Emergency Nursing. 2020;53:100917https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100917ArticlePubMed

- 32. Abdollahi A, Taheri A, Allen KA. Perceived stress, self-compassion and job burnout in nurses: The moderating role of self-compassion. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2021;26(3):182-191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120970612ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Kim SH, Yang YS. A meta analysis of variables related to burnout of nurse in Korea. Journal of Digital Convergence. 1015;13(8):387-400. https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2015.13.8.387Article

- 34. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- 35. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186ArticlePubMed

- 36. Gim WS, Park DH, Shin KH. Self-compassion, other-compassion, mindfulness, and quality of life: Comparing alternative causal models. The Korean Journal of Health Psychology. 2015;20(3):605-621.Article

- 37. Sansó N, Galiana L, Oliver A, Tomás-Salvá M, Vidal-Blanco G. Predicting professional quality of life and life satisfaction in Spanish nurses: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(12):4366https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124366ArticlePubMedPMC

- 38. Jeong JR, Shin SY. Influence of job stress, compassion satisfaction and resilience on depression of nurses. Korean Journal of Occupational Health Nursing. 2019;28(4):253-261. https://doi.org/10.5807/kjohn.2019.28.4.253Article

- 39. Delaney MC. Caring for the caregivers: Evaluation of the effect of an eight-week pilot mindful self-compassion (MSC) training program on nurses’ compassion fatigue and resilience. PloS One. 2018;13(11):e0207261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207261ArticlePubMedPMC

- 40. Kim YN. The influence factors on nursing work performance by clinical nurses. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society. 2022;23(1):594-602. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2022.23.1.594Article

- 41. Hwang EH. Comparison of resilience between novice and experienced nurses. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society. 2018;19(10):530-539. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2018.19.10.530Article

- 42. Sawyer AT, Bailey AK, Green JF, Sun J, Robinson PS. Resilience, insight, self-compassion, and empowerment (rise): A randomized controlled trial of a psychoeducational group program for nurses. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2021;https://doi.org/10.1177/10783903211033338Article

- 43. Garcia ACM, Silva BD, da Silva LCO, Mills J. Self-compassion in hospice and palliative care: A systematic integrative review. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2021;23(2):145-154. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000727ArticlePubMed

- 44. Zeybekçi S. Experiences of oncology nurses regarding self-compassion and compassionate care: A qualitative study. International Nursing Review. 2022;69(4):432-441. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12747ArticlePubMed

- 45. Jang MH, Jeong YM, Park G. Influence of the subfactors of self‐compassion on burnout among hospital nurses: A cross‐sectional study in south Korea. Journal of Nursing Management. 2022;30(4):993-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13572ArticlePubMed

- 46. Beaumont E, Durkin M, Hollins Martin CJ, Carson J. Measuring relationships between self‐compassion, compassion fatigue, burnout and well‐being in student counsellors and student cognitive behavioural psychotherapists: A quantitative survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2016;16(1):15-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12054Article

- 47. Fetter KL. We grieve too: One inpatient oncology unit's interventions for recognizing and combating compassion fatigue. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2012;16(6):559-561. https://doi.org/10.1188/12.CJON.559-561ArticlePubMed

- 48. Upton KV. An investigation into compassion fatigue and self-compassion in acute medical care hospital nurses: A mixed methods study. Journal of Compassionate Health Care. 2018;5(1):1-27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-018-0050-xArticle

- 49. Dev V, Fernando III AT, Kirby JN, Consedine NS. Variation in the barriers to compassion across healthcare training and disciplines: A cross-sectional study of doctors, nurses, and medical students. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2019;90:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.015ArticlePubMed

References

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Appendix 2.

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Figure

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite