여성근로자의 심장건강증진 프로그램의 통합적 고찰

An Integrative Review on Heart Health Promotion Programs for Female Workers

Article information

Abstract

본 연구는 여성 근로자의 심장건강증진 프로그램을 통합적으로 고찰한 연구이다. 논문 검색 결과 최종 7편의 논문이 선정되었으며, 1편의 논문만이 유사실험설계였고, 나머지의 경우 무작위대조 실험 설계로 진행된 연구였다. 프로그램 적용 기간은 대부분 12주였으며, 길게는 6개월까지 진행된 연구도 있었다. 대부분의 연구에서는 신체활동이 포함되는 프로그램을 적용 후 여성근로자들의 건강을 측정했으나, 구체적인 프로그램 내용은 찾아보기 어려웠다. 또한 심장건강에 영향을 주는 요소 중 사회심리적 건강도 있으나 프로그램에 포함되지 않았다. 따라서 향후 여성근로자 대상의 심장건강증진 프로그램 개발 시 사회심리적 건강이 포함되어야 할 필요성을 제언한다.

Trans Abstract

Background

The study aimed to identify the core components and the limitations of the programs to improve the heart health among female workers.

Methods

An integrative review was used, and the research from 1984 to 2021.

Results

Seven studies of the heart health promotion program among female workers were included. All of the studies included physical activities and was found that most of the intervention were effective in promoting heart health. However, most of the studies did not mention the details of the intervention. Although studies reviewed in this paper included psychological factors as outcome measure, none of the intervention included psychological contents.

Conclusions

This review can serve as a guidance to develop the standardized heart health promotion programs among female workers including not only physical activities but also psychological contents.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease accounts for the highest proportion of deaths worldwide over the past 20 years, especially among 55.4 million deaths worldwide in 2019, about 16% (89 million) died of ischemic heart disease [1]. The risk of cardiovascular diseases in the working population is increasing with the growing aging working population. Worker aged more than 55 years have increased by 6.7% over the last 10 years [2]. Also, among workers, 745,000 deaths from stroke and ischemic heart disease in 2016, which is a 29% increase since 2000 [3]. However, cardiovascular diseases can be mostly prevented by modifying heart-healthy behavior such as tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and harmful use of alcohol [4].

Workers experience lack of exercise, irregular diet, and high occupational stress [5-7], and these poor heart-healthy behavior and high occupational stress among workers are associated with heart health related problems (i.e., diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) [8,9]. Heart health related problems among workers have negative effects on productivity [10,11] and it leads to an increase of medical costs [12]. Therefore, continuous heart health promotion efforts are needed for workers.

Various types of heart health promotion programs are being implemented worldwide [13]. Although male and female have different biological, psychological, and social characteristics, most of these programs do not differentiate between male and female. Also, female have some vulnerable factors that can affect their health such as inequalities, psychosocial factors, and role overload in family [14]. De Sio et al. [15] reported that female workers, compared to male, were more vulnerable to workplace-related psychosocial risks including inequalities related to workload, decisionmaking autonomy, and organizational change and these risks increased their psychosocial stress. In addition, female workers have dual obligations at work and at home and experience more conflicts due to dual obligations than male workers [16]. Theses work–family conflicts affected the level of mental health, functioning through the two sequential mediators of negative affect and perceived stress [17], and depression [18]. If female workers continue to experience negative psychosocial status, it can have negative effects not only family health problems but also women's health problems and poor work efficiency [16]. Ryu et al. [19] also highlighted that among female workers, the risk of cardiovascular disease has been reported to increase about 125 times in 60s compared to those in 40s. Therefore, it is necessary for heart health promotion programs to be specific for female workers and an approach to improve heart health is needed considering psychosocial factors.

In this study, an integrated review was attempted to explore what contents and methods the program was provided and what effects were reported with such a program to develop a heart health promotion program for female workers. Since this review research method identifies attributes important for nursing intervention and derives results for specific phenomena as attributes or topics, it shows characteristics that are easy to find the basis for nursing practice [20]. Through this comprehensive review, we would like to give female workers some guidance to be useful for developing an effective heart health promotion program for female workers.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design

It was the integrative review about researches on heart health promotion programs for female workers. The research from 1984 to 2021 and those written in English were included.

2. Procedure

The methodology used in this paper was recommended by Whittemore and Knafl [20] which include 5 stages. The first stage is about identifying the problem. At the initial stage of the research meeting, the researchers agreed on the purpose and the boundaries of the study. Although there were many health promotion programs for the female workers, the standard health promotion program especially focused on heart health was not present. Therefore, there research problems were as follows: ‘What is known about heart health promotion programs for female workers?’ and ‘What types of heart promotion programs for female workers are present?’ The study aimed to identify the core components and the limitations of the programs in order to provide a guide for future studies and the programs to improve the heart health among female workers.

The second step is to find all meaningful and appropriate data step by step in line with the research topic, and for this purpose, the process was recorded in detail to increase reliability and accuracy of literature search in this study. After going through the coordination process of the two researchers through the meeting, the following final analysis criteria were prepared by revising and supplementing them. The specific selection criteria and exclusion criteria were as follows.

First, as a selection criterion, we searched and reviewed the literature according to PICO-SD (participants, intervention, comparison, outcomes, study design), which were key question strategies. The subjects of the study (P) were female workers who participated in heart health promotion program, intervention (I) was selected as the programs for preventing heart health. Heart promotion program should include improving cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as lipid, obesity related factors, diabetes related factors, heart function related factors, blood pressure, and cardiovascular risk factors. The comparison target (C) was selected as a control group that was not provided with intervention or a control group that applied the existing education method rather than the intervention presented in the paper. In the result (O), only papers measuring heart health related variables (i.e., cardiovascular disease risk factor measure, behavior related measure, psychological status) were included. Research Design (SD) did not limit the type of study to comprehensively confirm the contents and results of the intervention program, and only studies published in academic journals were included in the literature. Research design excluded protocols, meta-analysis, systematic literature review, non-original research or degree papers, books, and gray literature.

Literature search and analysis were conducted from September 12 to September 27, 2021. The publication year of search papers were those published until September 2021 which applied heart health promotion programs to female workers. Papers were searched by Research Information Sharing Service (RISS), Korea Studies Information Service System (KISS), CINAHL, PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane. The main keywords used in the thesis search were ‘woman’, ‘female’, ‘worker’, ‘heart’, ‘cardiovascular’, ‘cardiometabolic’, ‘metabolic’, and ‘health promotion’, and searched in combination.

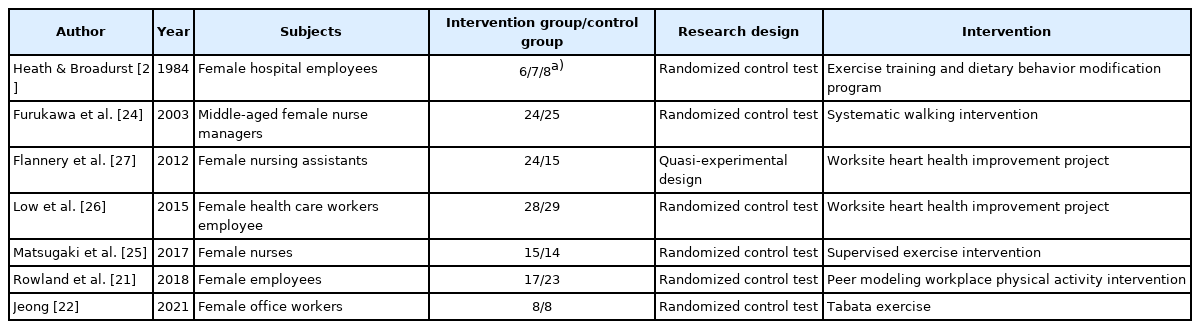

The third stage is evaluating data among researchers and determining and evaluating the suitability of each study. According to Whittemore and Knafl [20], due to diverse empirical source, applying a specific assessment tool to evaluate the quality of researches is not appropriate. Therefore, applying clear inclusion and exclusion criteria of the authors was important. In this study, the two authors, registered Nurses who have the doctoral degree on Nursing Science checked the data of the publication, name of the journal, research design, intervention method and type, duration, tools used in the study to fill out a matrix and evaluated the quality of each study. These were the criteria to include or exclude the study to this review. Through independent evaluation of the studies and active discussion between the authors, the discrepancies were resolved. As a result, 7 studies [21-27] were selected as suitable and analyzed for the final review (Fig. 1).

The fourth stage is analyzing data through interpretation without bias. To reach an integrated result, Whittemore and Knafl [20] mentioned that providing a matrix was needed to see what categories apply to each study. The collected data were categorized according to the analysis method or the research design, characteristics, and etc. In the matrix, all the information in the categories must be mentioned and must allow repeated comparisons. For the intervention studies, it was important to distinguish the differences and similarities describe the variables, and find intervention factors to make logical connections. Therefore, this study mentioned the matrix of the research as shown in Table 1.

The last stage is presenting the concept and attributing into a diagram or a table. To promote the understanding of the effects and the contents of the heart health promotion programs in the female workers, the integrative review were performed as is shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Results

1. Characteristics of included studies

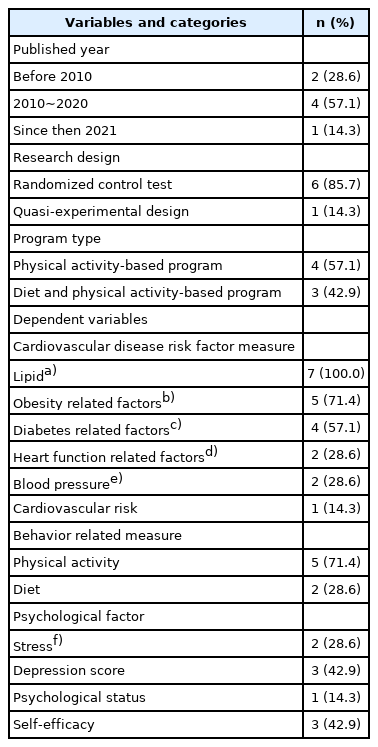

Among the studies searched, 7 studies (100%) [21-27] met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Hearth health promotion programs have been studies for a long time, but not many studies have been done among female workers. Studies from 2010 were actively performed. 6 studies (85.7%) [21-26] were randomized controlled test, but the numbers of the participants in the study were too small. All 7 studies (100%) [21-27] had experimental and control group. Among 7 studies [19-25], 4 studies (57.1%) [22,24-26] only used physical activity-based program, and other 3 studies (42.9%) [21,23,27] used both diet and physical activity-based program. When heart health promotion programs were conducted, most of the studies lasted 12 weeks. However, the duration of each session, and the frequency were varied (Table 3).

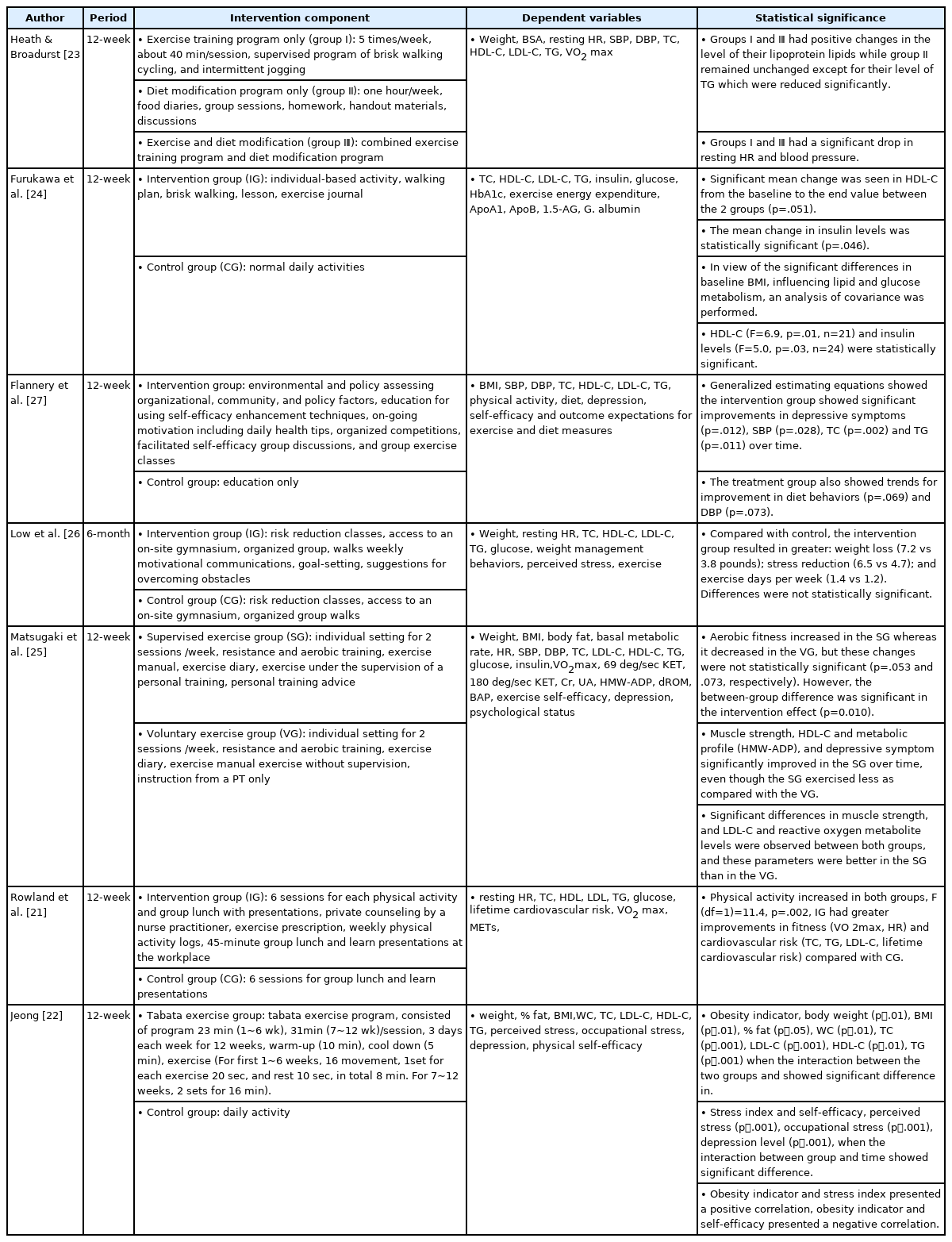

2. Contents of heart health promotion intervention

Heart health promotion intervention included physical activity and the diet controlled programs (Table 1). Among 7 studies, 4 studies [21-24] included physical activity alone for the intervention group, and other 3 studies [25-27] included supervisions, educations, and diet programs. All 7 studies [21-27] included physical activity as an intervention. However, types of the physical activities were various. A couple of studies only included aerobic exercise such as walking [24] only, walking, cycling, and intermittent jogging [23]. Other two studies included both resistance and aerobic training [22,25]. According to the studies physical activities were mostly effective in weight loss and in improving cardiovascular health. Although physical activities with diet associated program were found to be more effective, only 2 studies [23,26] included in the program. Also with a regular supervision of physical activity was found to be more effective than the programs with physical activity alone [25], only one study was included in the study.

Among the control groups of the studies, two control group did perform physical activity but without any supervision or education [25,26]. Although control group did performed exercise of their own, the effectiveness on the heart health did not improve significantly compared to the intervention group. The control group of 3 studies [22,24,27] did not do anything to the control group, therefore there was no difference in heart health.

Although physical activities implemented to the intervention groups were found to be effective to the heart health, not many studies explained details about the contents of the exercise. Only three studies [22,24,25] mentioned the details of the intervention protocol.

3. Effect of heart health promotion program and dependent variables

The effects for the programs were evaluated through the outcome measures. The outcome measures include cardiovascular disease risk factors (i.e., lipid, obesity related factor, diabetes related factor, heart function related factor, blood pressure, and cardiovascular risk), health behavior (i.e., physical activity and diet), and psychological factor (i.e., stress, depression, self-efficacy, and psychological status). Among the cardiovascular disease risk factors, all studies measured lipid level (i.e., total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides) and 5 studies (57.1%) [22,23,25-27] measured obesity related factors (i.e., weight, waist circumference, body mass index, body fat, and body surface areas). Among health behavior, 5 studies (71.4%) [21-25] measured physical activity.

All of heart health promotion program for female workers were found to be effective in controlling cardiovascular disease risk factors. According to the studies [22,25-27] included psychological factors, it is found that the psychological factors affected the heart health.

Discussion

Cardiovascular disease is becoming more common and it is known as one of the first cause of death related to work. Also it is known that cardiovascular problems have a negative effects on productivity [10,11] among workers. Especially, female workers are more vulnerable to psychological risks which relates to overall health [22]. Therefore, through this integrative review, we tried to explore the trend of the intervention among female workers and to suggest evidence for developing an effective heart health promotion program for female workers.

As a result of this review, all 7 studies included physical activity as an intervention for heart health promotion with control group. The contents of the studies for promoting heart health of the female workers was revealed that physical activities were effective on promoting heart health. Although diet was an important factor in cardiovascular health [26], only two studies included in the intervention. The contents of the diet program were writing food diaries and classes about nutrition. Since it did not mention the details of the diet program, it was hard to know what kind of diet program was more effective in promoting heart health among female workers.

Although studies reviewed in this paper included psychological factors as outcome measure [22,25-27], none of the intervention included psychological contents. Systematic review about work-related psychosocial factors [28] showed conflicting results about the relationship between psychosocial factors and cardiovascular disease. However, prospective studies [29] showed psychosocial factors, especially job strain, were related to increased cardiovascular disease risk. Nevertheless, health care workers have focused on the management of traditional risk factors based on the results of heart health related studies [13,21,23-25,30], such as high blood pressure, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, smoking, and lack of exercise, to manage heart health. Few studies included psychosocial factors such as stress and depression to promote heart health [30,31]. The lack of understanding and interest in psychosocial factors of health care workers and researchers can eventually be another risk factor for heart health [32], so they need to be interested in psychosocial factors for heart health promotion.

The period of the physical activities were mostly 12 weeks [21-25,27] and one study was 6 months [26]. However, the frequency of the intervention varied from biweekly to 5 times per week. Since the effect of the physical activity cannot show dramatic change within 12 weeks, the physical activity needs to be performed longer.

Also, only three studies [22,24,25] mentioned details of the intervention protocol. Due to lack of the details and varieties of the intervention, it was hard to compare which contents was more appropriate to the female workers and to standardized protocol to promote heart health programs among the female workers.

There are also many heart health promotion interventions [33-35] related to eating habits and physical activity for male workers, because diet and physical activity were linked to heart health [8,9]. Meanwhile, female workers suffer from workplace-family conflict and high psychological pressure and stress due to difficulties in simultaneously working at work and at home [15-18]. Pressure caused by multiple role burdens increases stress, negatively affecting health [36]. Stress of female workers play as mediators in the relationship between work–family conflict and health [37]. In addition to the contents of the heart health promotion program for male workers, which includes contents related to health behavior, heart health promotion programs among female workers need to include psychological contents.

The limitation of this review is as followed. First, due to lack of the details of intervention protocols, we cannot guide the standardized hearth health promotion intervention among female workers. Especially, psychological factors were not included in the reviewed studies, so we cannot guide what kind of intervention needs to be included as psychological intervention. Second, since we did not categorize the subjects as types of occupation, it is hard to generalize the effect of the intervention to all types of occupation.

Although there are limitations, this review has a few strengths. First, the trend of female worker heart health promotion program was explored. Second, through this review, the weakness and the strength of the intervention were revealed. Lastly, it could guide the contents of the future intervention which could be a standardized program for female workers.

In this study, we performed the comprehensive review on the heart health promotion programs among female workers. As found in this paper, the contents and the dependent variables of heart health promotion programs were varied. Although most of the programs included physical activity, none of the program included psychological contents as important. Therefore, we hope that this review can serve as a guidance to develop the standardized heart health promotion programs among female workers including not only physical activities but also psychological contents.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant number: NRF-2021R1 I1A1A01042277).