Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > STRESS > Volume 28(4); 2020 > Article

-

Original Article

흰쥐에서 장기간 구속 스트레스 노출이 혈장 Corticosterone 농도와 시상하부 산화질소 합성효소 활성 변화에 미치는 급성 및 만성 효과 -

박지혜

, 임인환

, 임인환 , 이서울

, 이서울

- Effects of Chronic Repetitive Restraint Stress on Acute and Long-Term Changes in Plasma Corticosterone Levels and Hypothalamic Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase Activity in Rats

-

Ji Hye Park

, Inhwan Lim

, Inhwan Lim , Seoul Lee

, Seoul Lee

-

stress 2020;28(4):285-291.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17547/kjsr.2020.28.4.285

Published online: December 31, 2020

1 원광대학교 의과대학 약리학교실

2 원광대학교 뇌과학연구소

3 원광대학교 의과대학 신경과학교실

1Department of Pharmacology, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Iksan

2Wonkwang Brain Research Institute, Wonkwang University, Iksan

3Department of Neurology, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Iksan, Korea

Copyright © 2020 by stress. All rights reserved.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,503 Views

- 24 Download

Key messages

- 흰쥐를 구속 스트레스에 7일 동안 반복하여 노출시킨 후 체중 변화, 혈장 corticosterone 농도, 시상하부 c-Fos, nNOS 활성, 청반 TH활성 및 탐색행동을 관찰하였다. 스트레스는 급성기 혈장 corticosterone 농도와 뇌실옆핵 c-fos, nNOS, 청반 TH 활성을 증가시키고 체중증가를 억제시켰다. 구속 스트레스를 중단하고 회복시킨 14일차에 측정한 만성기 corticosterone 농도와 nNOS활성 증가는 지속되어 있었다. 흰쥐에게 장기간 구속 스트레스는 혈장corticosterone과 시상하부 nNOS 활성을 증가시켰으며, 스트레스 중단 후에도 증가현상은 유지되었다. 이 결과는 스트레스에 의한 생리적 부적응으로 보이며, 시상하부 nNOS 활성 증가가 원인으로 사료된다.

Abstract

-

Background

- Immobilization as restraint stress is recognized as a psychologically stressful event. The stress responses alter both neuroendocrine and neurochemistry in an acute and long-term manner. We investigated whether the effect of chronic repetitive restraint stress could elicit levels of corticosterone and related neurochemical alterations.

-

Methods

- Nine-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats (the stressed group) were subjected to restraint stress in a hemi-cylindrical apparatus nocturnally in seven consecutive days. The handled control group was a sustained-controlled husbandry, and the stressed group was returned to the same home cage immediately after daily restraint sessions. On day 14, all subjects were sacrificed and neurochemical assessment was performed. Plasma corticosterone levels were measured on days 1, 7, and 14 following a 7-day recovery period. The activity of exploration was measured on day 5 of the stress session for 5 min to expose the novel open field. On day 14, tyrosine hydroxylase, c-fos, and NADPH-diaphorase immunohistochemistry was performed in the locus coeruleus and hypothalamic PVN (paraventricular nucleus) in the brain, respectively.

-

Results

- The repetitive restraint stress elicits a retarded growth pattern and lowers locomotive activity at the acute phase. During the stressed session, higher levels of plasma corticosterone and nNOS (neuronal nitric oxide synthase) activity in the hypothalamus. Furthermore, the upregulated changes were prolonged seven days after the stress-free recovery period, chronically.

-

Conclusions

- Chronic repetitive restraint stress may acutely alter neuroendocrine and behavioral changes via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and its phenomenon is sustained as a physiological maladaptation, depending on neurochemical alterations related to hypothalamic nNOS activity.

- 스트레스(stress)에 대응하여 신체에는 여러 가지 변화가 생기는데, 특히 중추신경계와 신경내분비계 반응에 동반되는 다양한 생리적 변동이 초래되고, 이러한 변화가 항상성에 영향을 미치게 되는 일련의 과정을 스트레스 반응(stress response)이라고 한다(Selye, 1973). 스트레스반응은 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신피질의 스트레스 대응축(stress axis; HPA axis)의 활성화로 부신피질호르몬(glucocorticoid)을 분비시키며, 교감신경-부신수질축의 활성화로 에피네프린(epinephrine)의 혈중 분비를 초래한다(Kim et al., 1998; de Kloet et al., 2005).

- Glucocorticoids는 다양한 스트레스에 의해 혈액으로 분비가 증가되는데, 사람의 경우 cortisol과 설치류인 흰쥐에서 corticosterone이 해당되며 신체적 에너지의 저장과 소화, 성장 및 염증반응을 억제하는 것으로 알려졌다(Sapolsky et al., 2000). 흰쥐에게 장기간 스트레스 노출은 부신 비대를 초래하며, corticosterone 분비를 증가시킨다고 보고되었다(Marin et al., 2007). 또한 스트레스에 의해 중추신경계에서 노르에피네프린(norepinephrine) 신경세포의 활성 증가가 보고되었으며(Hernández-Pérez et al., 2019), 카테콜아민 신경전달물질 생성속도 제한 효소인 tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) 활성화는 스트레스 반응 초기에 시작된다(Sabban et al., 2015). 이와 같은 스트레스에 의한 노르에피네프린 신경전달의 활성 증가는 정신 질환(psychiatric disorders)과 관련되어 있다고 알려져 있다(Itoi et al., 2010).

- 그렇지만, 스트레스가 일과성으로 단순하게 종결되지 않고 오랜 기간 동안 지속되거나, 또는 신체의 과도한 스트레스 반응에 의하여 glucocorticoids의 지속적인 분비가 일어나면 ‘생리적 부적응(physiological maladaptation)’을 초래하게 된다(Bowman, 2005). 여기에는 구조에 관련하여 신경세포의 성장 모양 또는 세포 사이 연접 형태의 변화가 수반되며, 중추신경계 활동의 외부 출력반응으로 인식되는 행동에서 변화가 관찰된다. 특히 이러한 구조와 행동 변이의 기저에는 신경계와 연결된 내분비계의 변동이 동반되는 것으로 알려져 있다(McEwen, 2007).

- 스트레스 대응과정에서 시상하부 뇌실옆핵(paraventri-cular nucleus, PVN)의 기능 조절이 매우 중요하며, 뇌에서 시작되는 스트레스 반응에 대한 역할을 담당하고 있다(de Kloet et al., 2005; Busnardo et al., 2019). 스트레스반응은 자극의 종류와 세기에 따라서 매우 다양한 형태로 표출되며, 시상하부에서 스트레스에 의한 신경화학적 반응에 관여하는 여러 인자들이 알려져 있다(Sabban et al., 2015). 뇌실옆핵 신경세포에서는 초기전사인자인 c-Fos가 스트레스반응 초기에 발현되며, 이것은 스트레스에 반응하는 신경세포의 활성화 정도를 나타낸다(Herdegen et al., 1998; Bienkowsky et al., 2008).

- 구속 스트레스는 많은 연구자들이 스트레스 반응에 대한 연구 방법으로 이용해 왔으며, 주로 사람의 경우와 비교하여 심리적 스트레스 인자(psychological stressor)로서 동물 실험에 이용하였다(Chiba et al., 2012). 흰쥐에서 장기간 구속 스트레스는 신경내분비계의 변화를 초래하는 동시에 면역체계를 억압시킨다고 알려져 있다(Thakur et al., 2017). 구속 스트레스는 혈액 내로 유리되는 corticos-terone 농도를 증가시키며, 뇌실옆핵, 전전두피질(pre- frontal cortex), 청반(locus coeruleus), 편도체(amygdala) 에서 다양한 신경전달물질의 유리에 관여하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Sabban et al., 2015). 또한 구속 스트레스는 신경가소성(neural plasticity)과 흥분성(neuronal excitability)을 조절한다고 알려진 신경성 산화질소생성효소(neuronal nitric oxide synthase, nNOS)의 활성을 뇌실옆핵 세포에서 증가시키며(Mancuso et al., 2010), 구속 스트레스에 의한 개체의 활동도 및 탐색행동의 저하는 산화질소생성효소 억제제를 투여한 경우에 회복되는 것으로 보고되었다(Masood et al., 2003).

- 이와 같이 스트레스에 의한 생체 내 반응은 다양하게 나타나지만, 극심한 스트레스에 의해 초래되는 생리적 변화와 행동 변동에 미치는 기전은 명확하게 밝혀져 있지 않다. 본 연구에서는 흰쥐를 장기간 반복 구속스트레스에 노출시켰을 때 혈액 내 corticosterone 농도, 시상하부 뇌실옆핵에서 c-Fos와 nNOS의 활성, 청반에서 TH 면역활성 및 탐색행동검사를 시행하여 중추에서의 신경내분비, 신경화학적 변화를 관찰하고 기전을 살펴보고자 하였다.

서 론

- 1. 실험동물(Animals)

- 체중 250 g 내외의 8주령 수컷 Sprague-Dawley 흰쥐를 샘타코(Samtaco Co., Osan, Korea)에서 구입하여 실험실 환경에 1주일 동안 적응시킨 후 실험에 사용하였다. 사육환경은 12시간 동안 낮과 밤이 되도록 일주기를 조절하였으며, 사육장 온도는 21±2℃, 습도는 50∼60% 로 유지시켰다. 사료(Rodent chow, Purina Co., Seoul, Korea)와 정수 처리된 물(purified tap water)은 자유롭게 섭취할 수 있도록 하였다. 실험동물은 대조군(Handled) 18마리와 스트레스군(Stressed) 18마리를 사용하였으며, 구속 스트레스 노출 다음날(1일)과 스트레스 노출 7일 후, 그리고 스트레스가 없는 1주일 동안의 회복기를 보낸 14일째 오전에 마취한 후 희생시켰다. 본 연구는 원광대학교 동물실험윤리위원회의 허가를 받았으며(승인 #WKU17- 110), 실험동물 관리와 이용에 관한 지침을 충실히 이행하였다.

- 2. 구속 스트레스(Restraint stress)

- 스트레스군 흰쥐는 바닥이 편평한 반원통 형태(hemi- cylindrical)의 아크릴로 된 규격화된 장치(Flat bottom rodent holder, Kent Scientific Co., CT, USA)를 이용하여 7일 동안 매일 19시부터 07시까지 구속하였다. 실험동물은 스트레스 투여 종료 직후 원래 사육장으로 이동시켰으며 물과 사료를 자유롭게 섭취할 수 있도록 하였다. 대조군은 체중 측정 시간만 제외하고 아크릴로 된 일반적인 사육장에서 사육시켰으며, 스트레스군이 구속되어 있는 동안에는 대조군도 동일한 시간 동안 물과 사료의 섭취를 제한하였다. 구속 스트레스가 종료된 후 7일 동안 대조군과 동일한 일반 사육장에서 스트레스를 주지 않은 회복기 7일을 두었으며, 이 시기에는 매일 오전 일정시간에 체중만 측정하였다.

- 3. 혈장 Corticosterone 농도 측정(Radioimmunoassay)

- 실험동물에게 구속 스트레스를 준 뒤 1일, 7일 그리고 회복기 7일을 지난 14일째 혈장 corticosterone 농도를 측정하였다. 실험일 오전에 흰쥐를 0.3 ml/kg Chloral hydrate, pentobarbital sodium mixture로 복강 내 주사하여 마취시킨 후 흉강을 절개하고 심이(auricle)에서 채혈하여 EDTA함유 혈액수집관(Vaccutainer, BD Co., CA, USA)에 넣은 후 혈장을 원심분리하고 −70℃ 냉동고에 보관한 후 실험에 사용하였다. Corticosterone 측정은 방사성 동위원소가 표지된 [125I]-corticosterone과 항체를 이용한 면역반응 검출법(Radioimmunoassay Kit; COAT-A-COUNT, DPC Co., CA, USA)으로 수행하였으며, 결과는 감마선량 측정기(Gamma Counter; Packard Instrument Co., CA, USA)로 측정하여 ng/ml 단위로 환산하였다.

- 4. c-Fos, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) 면역조직화학 염색

- 흰쥐를 복강 내 주사로 마취시킨 후 heparin 5 units가 함유된 생리식염수를 좌심실을 통해 관류하여 혈액을 제거한 다음 4% paraformaldehyde (in 0.1 M Phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4) 고정액을 관류시켜 조직을 고정하였다. 뇌를 적출하여 고정액에서 2시간 후고정과정을 거친 후 30% sucrose 용액에 2일 동안 방치한 다음 면역조직화학(immunohistochemistry)을 시행하였다. 뇌조직을 냉동조직박절기(Cryotome, Reica Co., Germany)를 이용하여 20 mm 두께로 관상면으로 박절한 후 얻어진 조직을 세척하고, 0.2% Triton X-100, 1% bovine serum albumin 함유 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline 용액에 처리하여 조직의 투과성을 개선하였다. 시상하부 뇌실옆핵이 있는 조직에서 1차 항체로서 anti c-Fos (Oncogene Co., MA, USA)과 청반에서 anti-TH (Immunostar Co., WI, USA)과 2차 항체로서 anti-rabbit Ig G, anti-goat Ig G (Vector Laboratory, CA, USA)를 사용하였다. 항체표식을 위해 avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratory, CA, USA)를 사용하였고, 0.006% hydrogen peroxide함유 3, 3’-diaminobezidine (Sigma Co., MO, USA)용액에서 5분 동안 발색시켰다.

- 5. NADPH-diaphorase 조직 이중 염색

- c-Fos 항체를 조직에서 발색시킨 다음 동일 조직으로 nNOS 활성을 NADPH-diaphorase (NADPH-d) 효소활성 염색 방법을 사용한 이중 염색으로 관찰하였다. 조직 절편을 0.1% Tris-Triton X-100 용액으로 37℃에서 10분 동안 전처리 과정을 거친 다음 0.25 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium, 1 mg/ml -NADPH (Sigma Co., MO, USA) 함유 0.1 M Tris 용액에서 효소반응(enzymatic reaction)을 시켰다.

- 6. 탐색행동 검사(Exploratory behavior test)

- 실험동물에게 구속 스트레스를 투여한 5일째 되는 날 활동도 측정 장치(Open-field activity monitor system; Med associates, VT, USA)를 이용하여, 개체가 새로운 환경에 노출되었을 때 나타내는 탐색행동을 5분 동안 측정하였다. 활동도 측정 장치는 투명한 아크릴로 된 상자(50×50×40 cm)위에 백색광을 켜 놓은 후 2.54 cm 간격으로 설치된 적외선 감지장치를 이용하여 움직임을 추적하는 것으로서 흰쥐가 움직이는 보행활동도(ambulatory activity)를 1분 간격으로 수집하여 분석하였다. 동일한 장치를 반복 사용하므로 일어날 수 있는 이전 실험동물의 분비물에 의한 다음 번 실험동물에 대한 영향이 최소화되도록 매번 70% 소독용 alcohol로 세척하고 건조하였다.

- 7. 통계 분석(Statistical analysis)

- 측정 결과는 평균±표준오차(mean±standard error [S.E.])로 표기하였으며, 대조군(Handled)과 스트레스군(Stressed)간의 유의성 검정은 StatView Ver. 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc.) 과 Prism Ver. 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.)을 이용하였다. 체중 비교는 2 way ANOVA (analysis of variance)로 15일 동안의 매일 측정 값을 비교분석 하였으며 유의수준 alpha=0.05로 Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test 결과를 Fig. 1에 표시하였고, 15일 동안 전체 비교는 repeated measures of ANOVA (analysis of variance)를 이용하여 분석하였다. 혈장 corticosterone농도 비교는 unpaired t-test로 two-tailed, 유의수준은 p< 0.05로 시행하였다. 탐색행동에서 보행활동도 비교는 2 way ANOVA로 5분 동안의 측정 값을 1분 간격으로 구분하여 비교분석 하였으며, 5분 동안 비교는 Repeated measures of ANOVA를 이용하여 분석하였다.

재료 및 방법

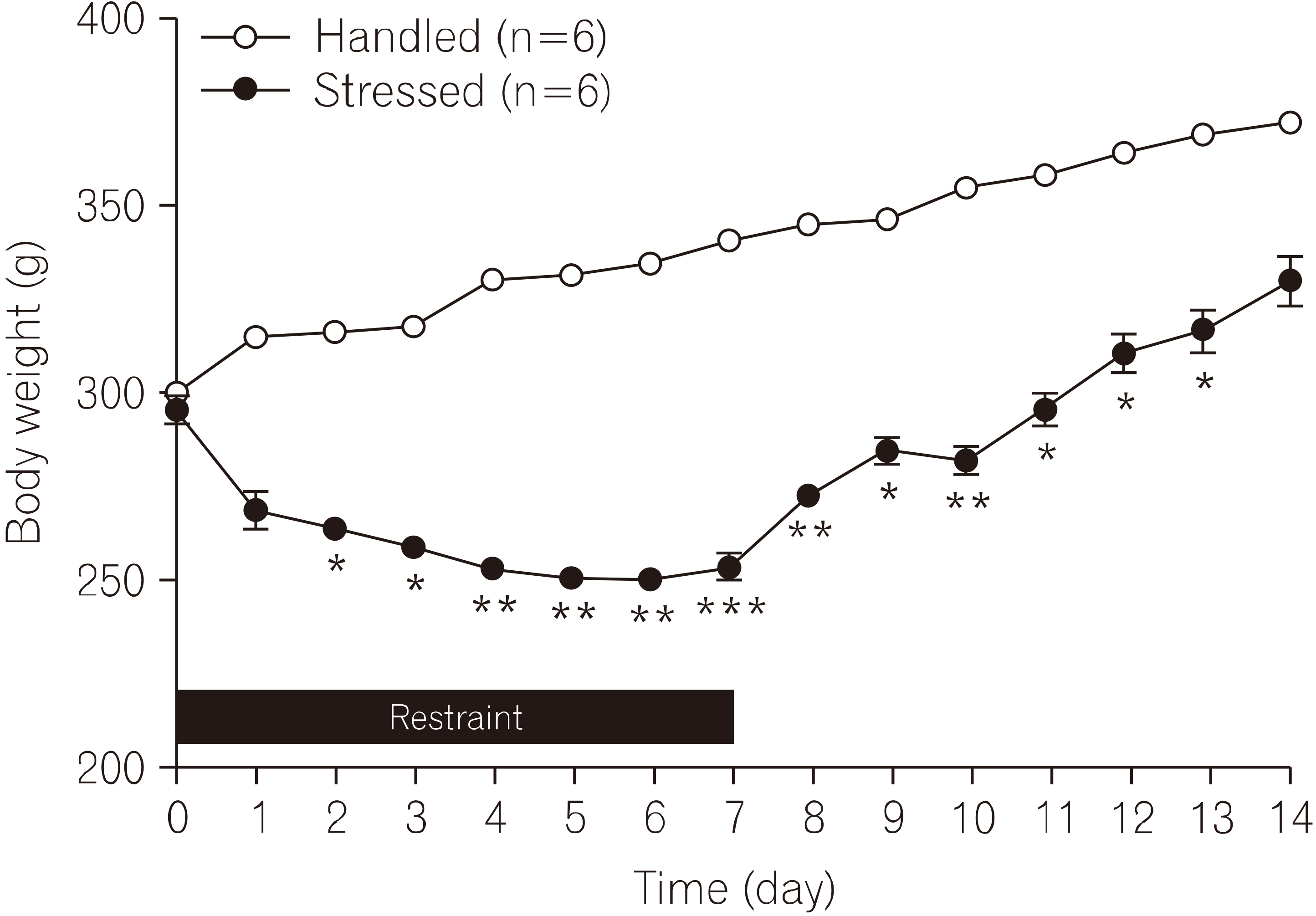

- 1. 구속 스트레스가 체중증가에 미치는 영향

- 구속스트레스 기간과 스트레스 종류 후 회복기동안의 실험동물의 체중증가를 측정하였다(Fig. 1). 흰쥐를 7일 동안 구속 스트레스에 노출시키는 동안 스트레스군의 체중은 대조군과 비교하여 감소되었으며, 이후 스트레스를 주지 않은 회복기 7일 동안에는 체중 증가는 관찰되지만 대조군의 체중에는 미치지 못하였다. 전체 실험 기간동안 측정한 스트레스군의 체중은 대조군에 비해 유의하게 감소되어 있는 것을 관찰하였다(F1, 14=126.2, p<0.001). 대조군과 스트레스군의 체중증가 정도는 구속 스트레스 1일에는 차이가 관찰되지 않았지만(t=0.95, p=0.318), 2일(t=8.76, p<0.001) 후부터 유의한 차이가 관찰되었으며, 구속이 종료된 이후 13일(t=8.65, p<0.001)까지 지속되었다.

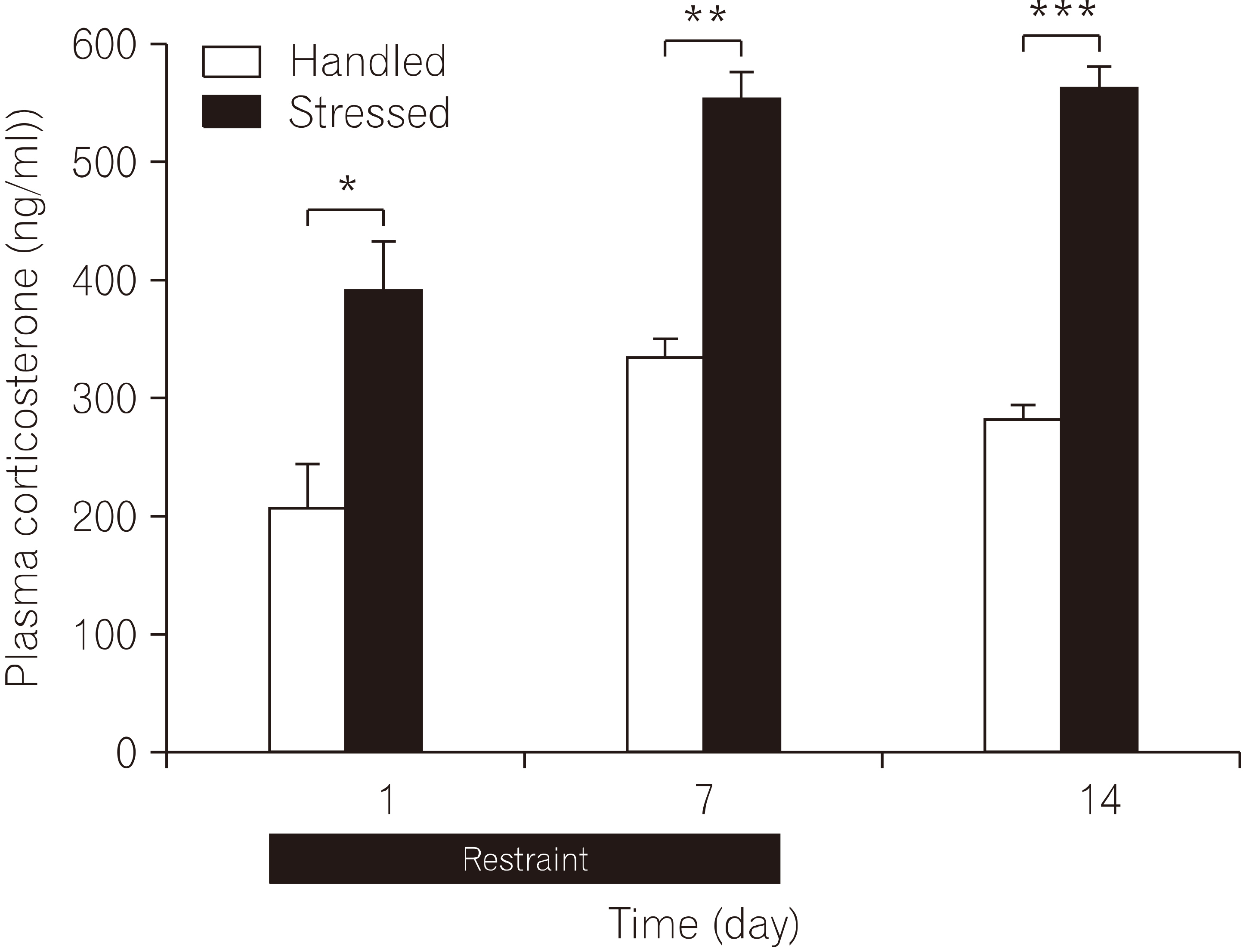

- 2. 구속 스트레스가 혈장 corticosterone 농도에 미치는 영향

- 실험동물을 구속 스트레스에 반복 노출시킨 후 1일, 7일, 회복기 7일이 지난 14일 후 혈액을 채취하여 혈장 corticosterone 농도를 측정하였다(Fig. 2). 구속 스트레스 경험 1일 후 혈장 corticosterone 농도는 스트레스군 353.1±28.4 ng/ml, n=4로 대조군 206.8±36.8 ng/ml, n=4에 비해 유의하게 증가되었다(t=3.15, p=0.019). 구속 스트레스를 반복하여 7일 동안 노출시켰을 때 혈장 corticos-terone 농도는 스트레스군 551.7±24.3 ng/ml, n=4로 대조군 360.1±38.2 ng/ml, n=4에 비해 유의하게 증가되었다(t=4.23, p=0.005). 구속 스트레스 노출이 종료된 후 스트레스가 없는 회복기 7일이 지난 14일 째 혈장 corticoste-rone 농도 측정에서 스트레스군은 562.0±16.2 ng/ml, n=5로 대조군 330.1±19.4 ng/ml, n=5에 비해 유의하게 증가되었다(t=9.18, p<0.001). 스트레스군의 혈장 corticosterone 농도 증가는 구속 스트레스 초기부터 시작되며 반복된 구속 스트레스 기간동안 증가가 지속되었고, 이 후 스트레스를 주지 않은 회복기 7일이 지난 후에도 증가가 지속되는 것이 관찰되었다.

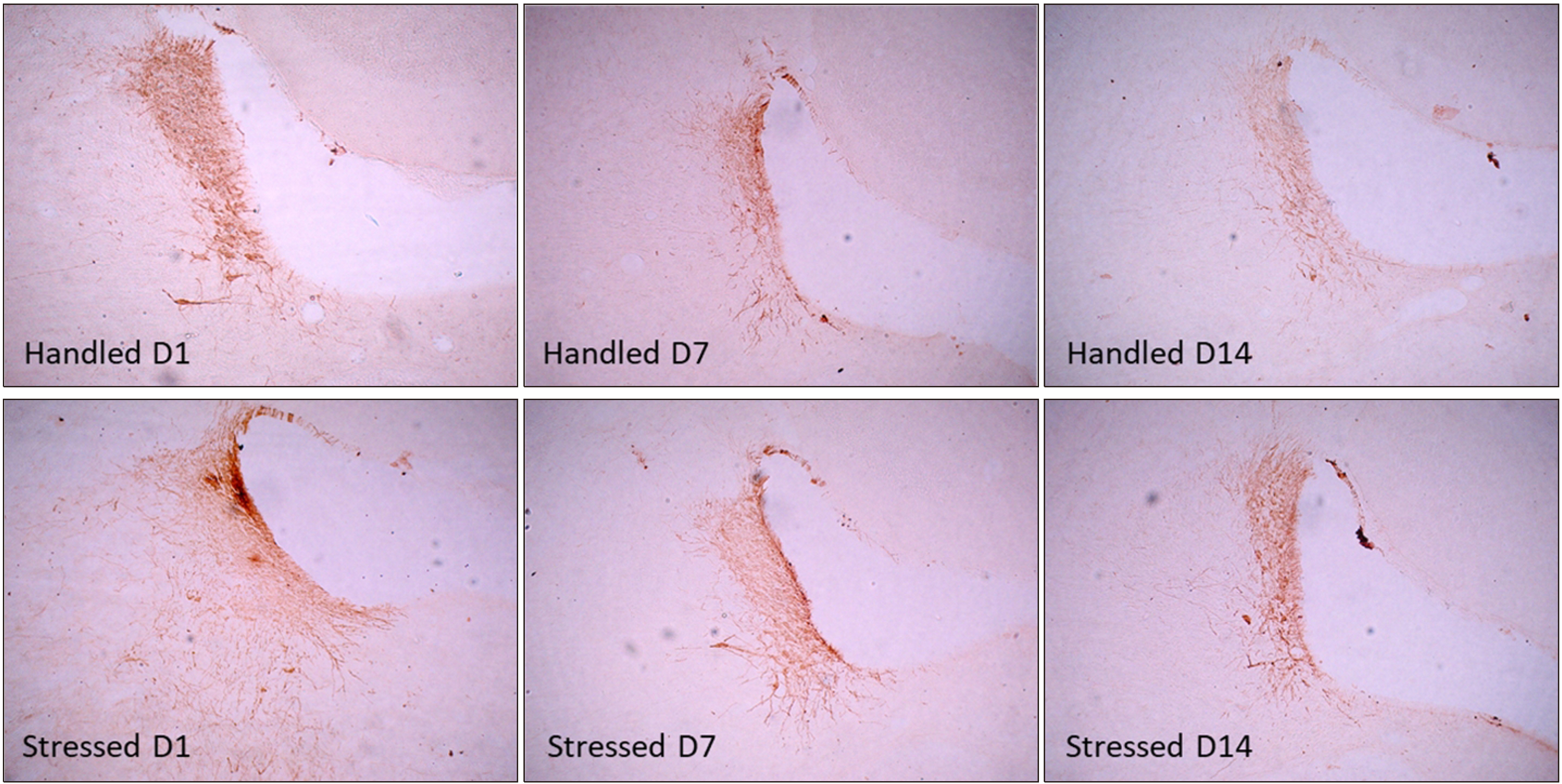

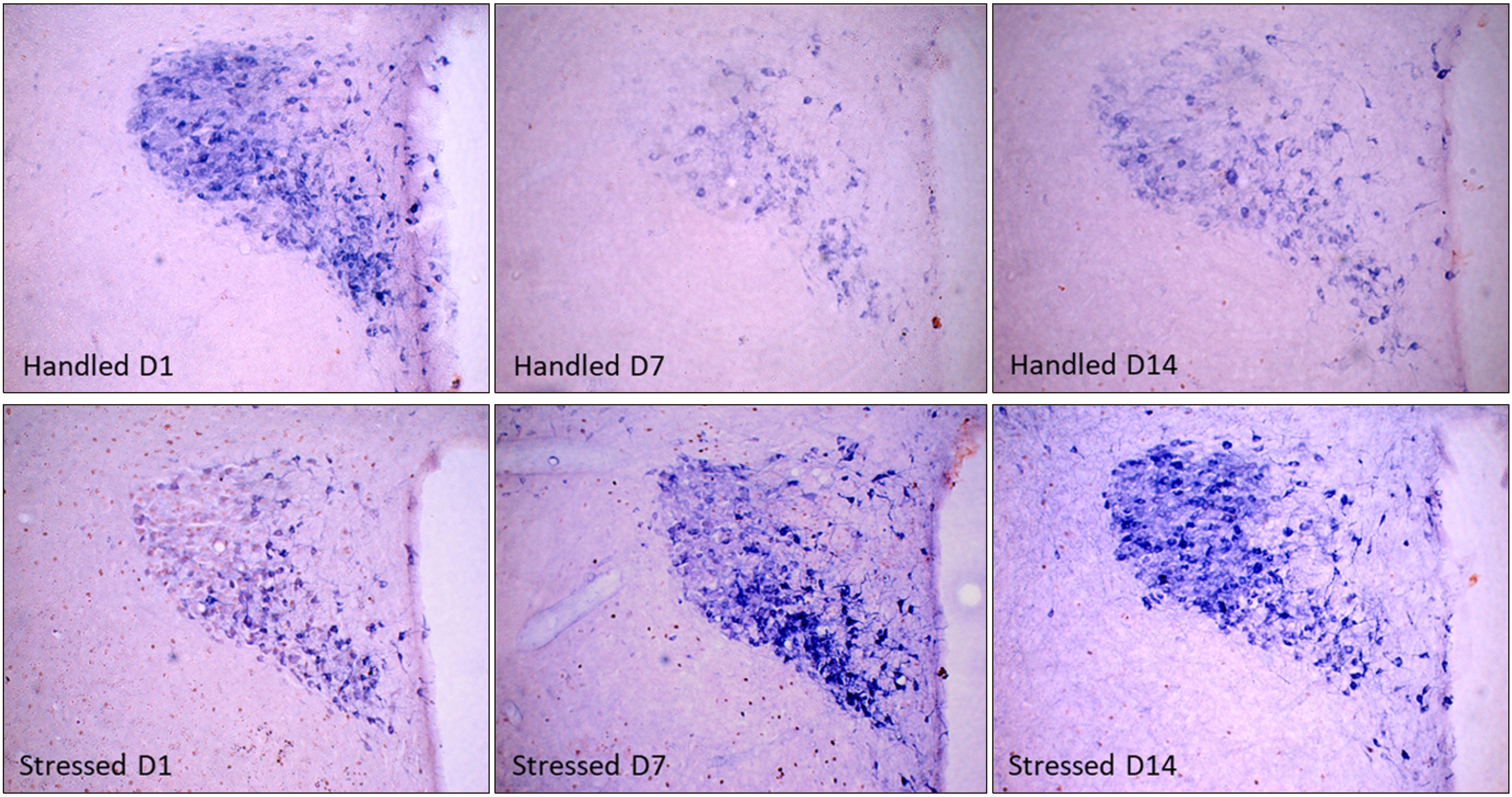

- 3. 구속 스트레스가 c-Fos 면역활성과 NADPH-diaphorase 효소활성에 미치는 영향

- 실험동물을 반복되는 구속 스트레스에 노출시킨 후 1일, 7일, 회복기 7일이 지난 14일 후 뇌 시상하부 뇌실옆핵에서 초기전자인자 c-Fos 면역활성과 nNOS 활성을 면역조직화학염색과 NADPH-d 효소활성을 이중 염색하여 관찰하였다(Fig. 3). 대조군의 c-Fos 면역활성은 극히 일부 세포에서만 관찰되었으나, 스트레스군의 경우 구속 스트레스 노출 1일 후 c-Fos 면역활성 세포 수는 크게 증가하였다. 스트레스 노출 3일 이후부터는 대조군과 비교하여 변화가 관찰되지 않았다. NADPH-d 효소활성을 나타내는 신경세포는 스트레스군에서 구속 스트레스 노출 초기부터 시작하여 7일 동안 증가되었으며, 이후 스트레스가 없는 회복기가 지난 14일 후에도 증가가 지속되는 것을 관찰하였다.

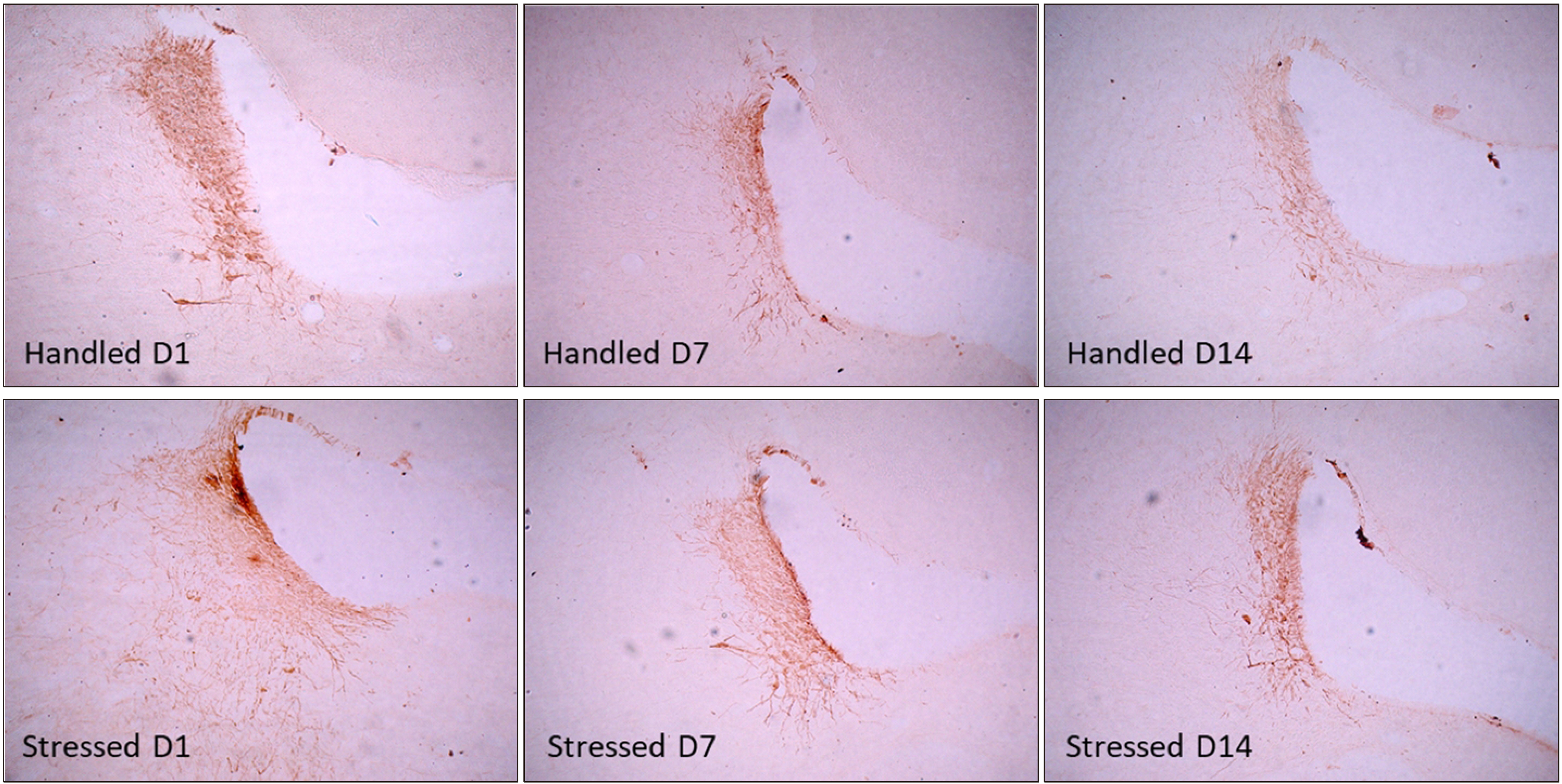

- 4. 구속 스트레스가 tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)면역활성에 미치는 영향

- 실험동물을 구속 스트레스에 노출시킨 후 1일, 7일, 회복기 7일이 지난 14일 후 노르에피네프린 합성 속도제한효소인 TH 면역활성을 청반에서 면역조직화학방법으로 관찰하였다(Fig. 4). TH 면역활성 정도는 구속 스트레스 노출 1일 후 스트레스군에서 대조군에 비해 증가되었으나, 7일 동안 구속한 경우와 이후 스트레스가 없는 회복기 7일이 지난 14일 후에는 대조군과 비교하여 변화가 관찰되지 않았다.

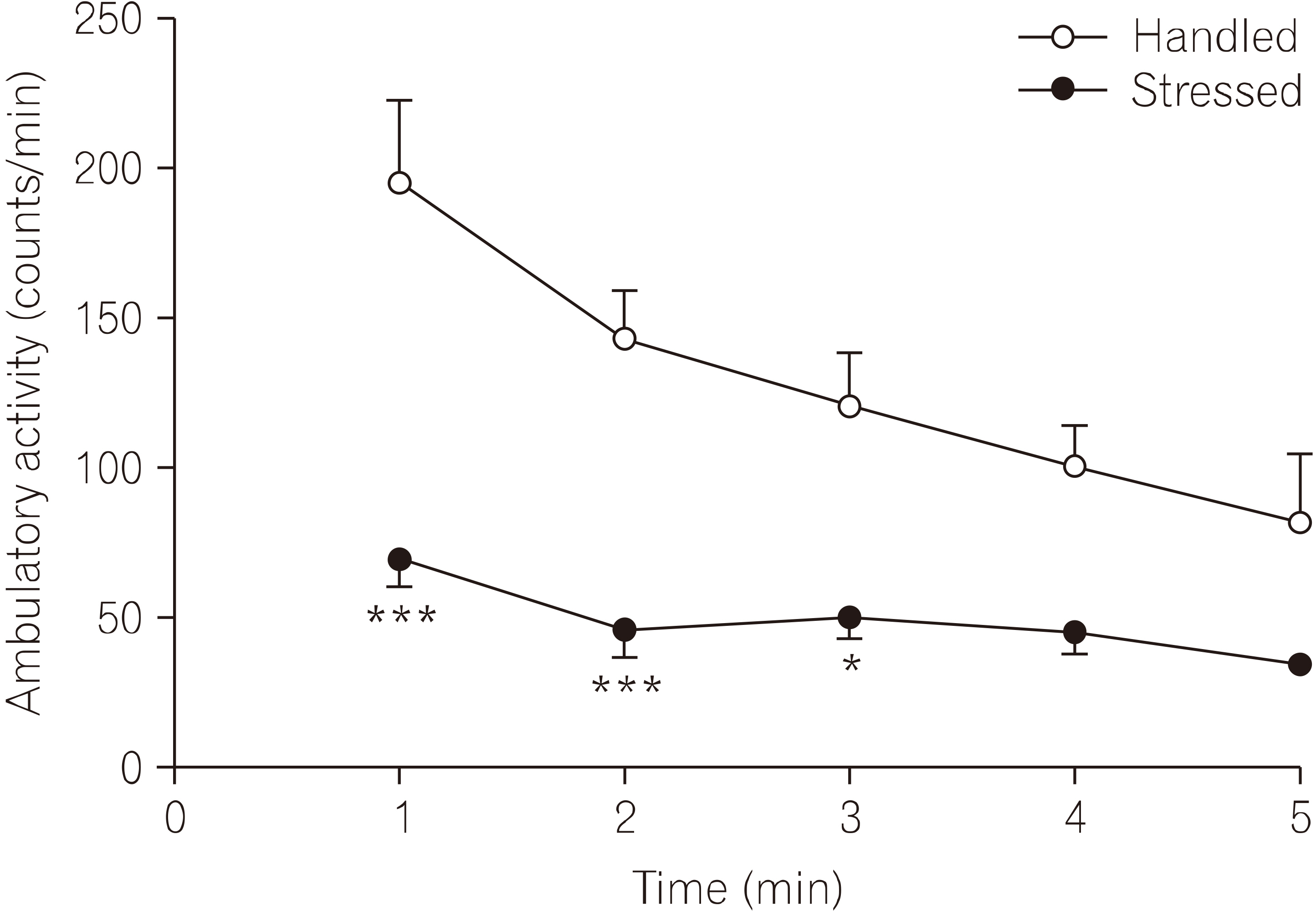

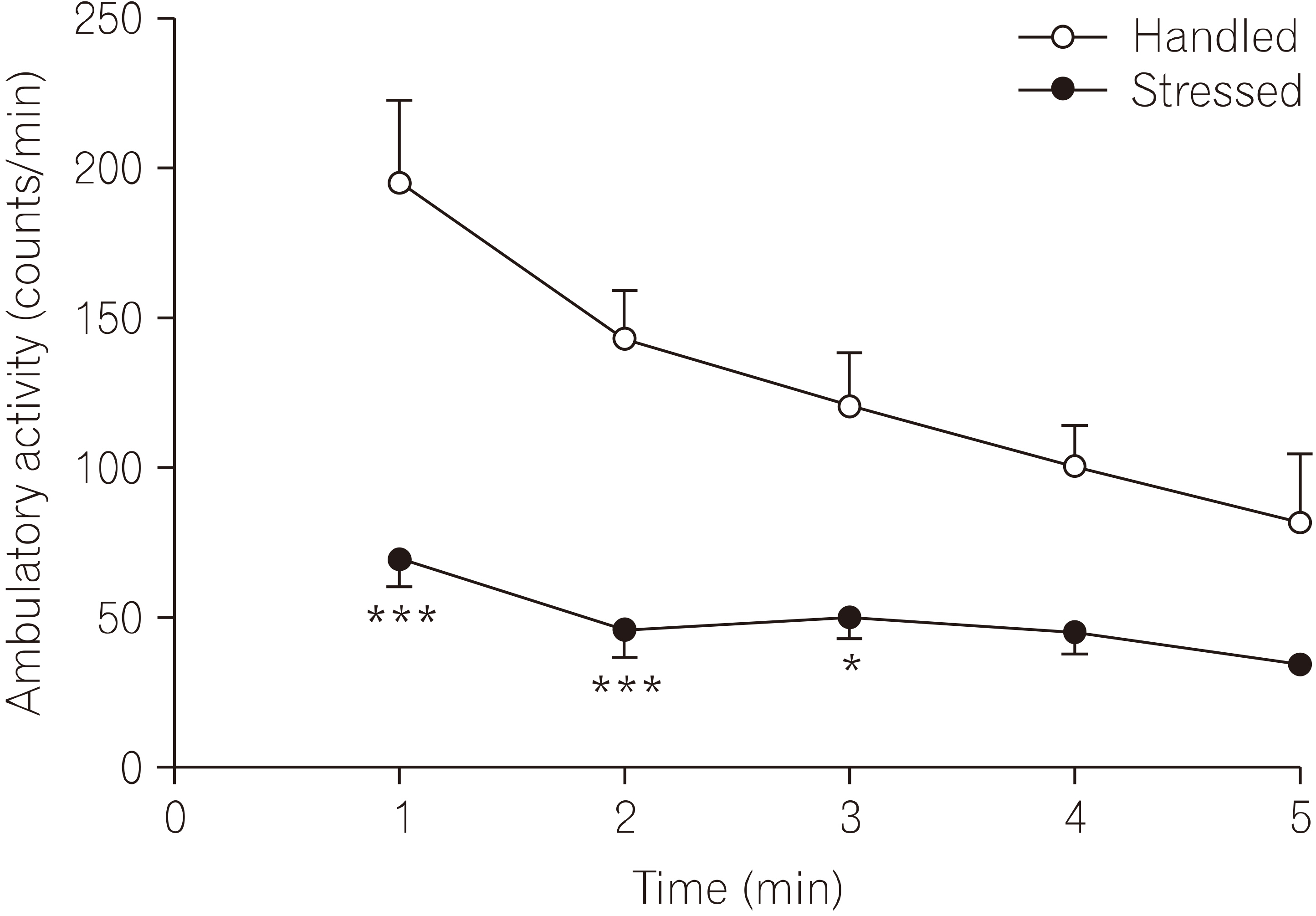

- 5. 구속 스트레스가 탐색행동에 미치는 영향

- 실험동물을 새로운 환경에 노출시켰을 때 나타내 보이는 탐색행동검사를 시행하여 5분 동안 보행활동도를 측정하였다(Fig. 5). 보행활동도 측정 결과 스트레스군의 활동도는 대조군에 비해 유의하게 감소되었다(F1, 30=66.12, p< 0.001). 처음 1분 동안의 보행활동도는 스트레스군 68.7± 9.5, n=4로 대조군 194.8±18.5, n=4에 비해 유의하게 감소되었다(t=5.80, p<0.001). 연속된 보행활동도 측정에서 4분 경과 후부터는 실험군사이에서 유의한 차이가 관찰되지 않았다.

결 과

- 흰쥐에 구속 스트레스를 반복하여 장기간 노출시킨 경우, 대조군에 비해 체중 증가 억제가 뚜렷하게 나타나는 것을 관찰하였고, 구속 스트레스가 종결된 이후에는 체중 증가가 뚜렷하게 나타나 회복되는 것으로 관찰되었다. 이것은 장기간 반복되는 구속 스트레스는 체중 증가 및 신체발달에 나쁜 영향을 초래하는 결과로 보여지는데, 다른 연구에서도 실험동물에게 3일 동안 반복하여 구속 스트레스를 가한 경우에는 corticosterone-releasing factor (CRF)의 급격한 증가와 더불어 장기간 체중 감소가 초래되었다(Harris et al., 2002). 또한 반복적인 구속 스트레스에 의한 체중 감소 효과는 CRF 수용체 길항제를 뇌실 내 투여한 경우에는 봉쇄되었다(Smagin et al., 1999). 본 연구에서 스트레스군의 경우 구속 스트레스에 노출되는 시간 동안에는 물과 사료의 섭취가 제한될 수밖에 없었으므로, 비교 대상인 대조군 또한 스트레스군과 동일한 시간에는 물과 사료의 공급을 제한하였다. 따라서 스트레스군의 체중 증가의 감소 및 억제는 구속 스트레스에 의해 유도된 신체의 스트레스에 대한 반응의 결과로 보인다. 구속 스트레스 노출 1일 후 측정한 혈장 corticosterone 농도는 대조군에 비해 스트레스군에서 유의하게 증가되었다(Fig. 2). 이 결과는 구속 스트레스는 스트레스인자로서 작용하여 corticosterone 농도를 증가시킨다는 보고와 일치하였다(Gong et al., 2015).

- 그러나 본 연구에서 구속 스트레스에 노출을 7일 동안 하였을 때와 이후 스트레스를 주지 않은 7일 동안의 회복기간이 지난 14일 후에 측정한 corticosterone 농도 변화 비교에서 스트레스군의 경우 대조군에 비해 유의하게 증가되어 있어(Fig. 2), 다른 연구에서 보고되었던 일과적 스트레스 노출에 의한 현상과는 차이가 있었다(Gong et al., 2015). 흰쥐에서 장기간 구속 스트레스 노출이 혈중 corticosterone 농도 변화에 미치는 영향은 스트레스에 노출된 기간과 노출시간에 따라 다르게 나타난다는 보고들과 비교하였을 때(Wang et al., 2002), 본 연구에서 혈장 corticosterone 농도 증가는 스트레스 노출 기간과의 상관성이 큰 것으로 생각된다. 이와 같은 결과는 일시적 스트레스 노출에 의한 현상과는 다르게 장기간 스트레스에 노출되었을 경우, 스트레스가 종결되었음에도 불구하고 스트레스에 대한 신체의 반응이 지속되는 현상이 나타난 것으로 보이며, 이와 같은 스트레스 반응의 지속 현상은 과도한 스트레스 자극 또는 과도한 신체의 스트레스 반응에 의한 ‘생리적 부적응’ 현상이 초래된 것으로 판단된다(Bowman, 2005).

- 즉시성 초기전사인자로 알려진 c-Fos는 신경세포의 활성화 정도를 나타낸다고 알려져 있으며(Ginsberg et al., 2003), 구속 스트레스 또는 전기충격 같은 스트레스 유발 자극에 의해서 c-Fos 단백의 면역염색활성이 증가된다고 보고되었다(Lin et al., 2018). 본 연구에서 구속 스트레스 노출 1일 후 시상하부 뇌실옆핵에서 c-Fos의 면역활성이 증가되었는데, 이것은 시상하부에서 c-Fos 활성 증가는 초기 스트레스 반응에 관여하고, 구속 스트레스에 의한 c-Fos 발현은 스트레스 초기에만 급격하게 증가된다는 다른 연구자의 결과와 일치하였다(Weinberg et al., 2007).

- 신경가소성과 흥분성을 조절하는 신경조절인자로 알려진 nNOS는 시상하부에서 활성화되었을 경우 신체의 스트레스 반응을 조절하는 시작점으로서 역할을 한다고 보고되었다(Masood et al., 2003). 본 연구에서 흰쥐에게 7일 동안 구속 스트레스에 노출시킨 경우 시상하부 뇌실옆핵에서 nNOS 효소활성이 증가되었으며, 스트레스가 종료된 후 7일 동안 회복기를 지난 후에도 증가된 효소활성이 지속되었다(Fig. 3). 이와 같은 결과는 흰쥐에서 구속 스트레스 노출은 뇌실옆핵에서 nNOS 활성과 nNOS mRNA 발현을 증가시키며(Orlando GF et al., 2008), 증가된 nNOS mRNA가 산화질소 신경전달을 통해 ACTH 유리를 조절한다는 다른 보고와 일치하였다(de Oliveira et al., 2000). 본 연구의 결과에서 스트레스가 종결된 이후에도 corticosterone 농도 증가가 비정상적으로 지속되는 ‘생리적 부적응’ 현상이 관찰되는 것은 시상하부 nNOS 활성 증가가 지속되기 때문에 나타나는 동반 효과로 생각된다.

- 구속 스트레스는 신경행동관련 연구에서 개체의 동기유발을 감소시키고, 이것은 탐색행동의 감소와 학습 장애도 동반한다고 알려졌는데, 본 연구에서 측정한 보행활동도(ambulatory activity)는 개체가 새로운 환경에 노출되었을 때 보여주는 탐색행동을 판단하는 지표로 알려져 있다(Kim et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2017). 또한 흰쥐에서 구속 스트레스에 의한 탐색행동의 저하는 신경조절인자로 알려진 nNOS 활성으로 인해 초래된다는 보고와 일치한다(Masood et al., 2003). 이를 확인하기 위하여 본 연구에서도 open-field 장치에서 최초 5분 동안 활동도를 측정한 결과(Fig. 5), 반복되는 구속 스트레스는 흰쥐의 보행활동도를 대조군에 비하여 유의하게 감소시켰으며, 본 실험에서 관찰된 구속 스트레스에 의한 보행활동도 저하는 시상하부 nNOS의 활성화에 기인되는 것으로 생각된다.

- 스트레스는 청반에서 노르에피네프린 합성 제한 효소인 TH mRNA 발현을 증가시키며, 교감신경 활성화 및 시상하부-뇌하수체-부신 반응축의 활성에 의해 TH 활성이 유도된다고 보고되었다(Boorman et al., 2017). 본 연구에서 구속 스트레스 노출 1일 후 청반에서 TH 면역활성은 대조군에 비하여 증가되었다. 그러나 구속 스트레스 7일 후와 스트레스 종료된 이후 7일 동안의 회복기를 지난 14일째 TH 면역활성은 대조군과 비교하여 차이가 관찰되지 않았다(Fig. 4). 흰쥐에서 청반 노르에피네프린 신경세포의 TH활성화 정도는 구속 스트레스 노출 초기에만 국한되는 것으로 여겨진다.

- 이상의 결과를 종합하면 흰쥐에게 장기간 반복적인 구속 스트레스 노출은 탐색행동에서 보행활동도 저하를 초래하였고, 혈중 corticosterone 농도 증가는 스트레스에 노출되는 기간에 국한된 것이 아니라 스트레스 종료 후에도 지속되었으며, 시상하부에서 nNOS의 지속적인 활성화가 수반되는 것을 관찰하였다.

- 본 연구에서 흰쥐를 장기간 반복되는 구속 스트레스에 노출시키면 급성기 스트레스 반응에서는 항상성 유지를 위한 일련의 정상적인 스트레스 반응이 유도되지만, 스트레스가 종료된 이후에도 스트레스에 의해 유도된 신체의 스트레스 반응은 종결되지 않고 지속되어 나타나는 일종의 ‘생리적 부적응’ 현상이 만성으로 초래되고 유지되고 있는 것을 혈장 corticosterone 농도가 고농도로 지속되는 결과로 확인하였고, 여기에는 스트레스에 대응하는 HPA 축의 시작점인 시상하부에서 특히 뇌실옆핵 부위에서 nNOS 활성 지속이 관련되어 있다고 사료된다.

고 찰

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

-

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

Funding

This research work was supported by Wonkwang University Research Grant in 2019.

Notes

- 1. Bienkowski MS, Rinaman L. 2008;Noradrenergic inputs to the paraventricular hypothalamus contribute to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and central Fos activation in rats after acute systemic endotoxin exposure. Neuroscience. 156(4):1093-102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.011.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Boorman DC, Kang JWM, Keay KA. 2019;Peripheral nerve injury attenuates stress- induced Fos-family expression in the Locus Coeruleus of male Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res. 156:253-262. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.06.007.Article

- 3. Bowman RE. 2005;Stress-induced changes in spatial memory are sexually differentiated and vary across the lifespan. J Neuroendocrinol. 17(8):526-35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01335.x.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Busnardo C, Crestani CC, Scopinho AA, et al. 2019;Nitrergicneurotransmissionintheparaventricularnucleusofthehypothalamusmodulatesautonomic,neuroendocrineandbehavioralresponsestoacuterestraintstressinrats. ProgNeuropsychopharmacolBiolPsychiatry. 17:16-27. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.11.001.Article

- 5. Chiba S, Numakawa T, Ninomiya M, et al. 2012;Chronicrestraintstresscausesanxiety-anddepression-likebehaviors,downregulatesglucocorticoidreceptorexpression,andattenuatesglutamatereleaseinducedbybrain-derivedneurotrophicfactorintheprefrontalcortex. ProgNeuropsychopharmacolBiolPsychiatry. 39(1):112-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.05.018.Article

- 6. de Kloet E, Joëls M, Holsboer F. 2005;Stress and the brain: From adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 39:463-475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683.Article

- 7. de Oliveira RM, Aparecida Del Bel E, Mamede-Rosa ML, et al. 2000;ExpressionofneuronalnitricoxidesynthasemRNAinstress-relatedbrainareasafterrestraintinrats. NeurosciLett. 289(2):123-126. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01287-8.Article

- 8. Ginsberg AB, Campeau S, Day HE, et al. 2003;Acuteglucocorticoidpretreatmentsuppressesstress-inducedhypothalamic-pituitary-adrenalaxishormonesecretionandexpressionofcorticotropin-releasinghormonehnRNAbutdoesnotaffectc-fosmRNAorfosproteinexpressionintheparaventricularnucleusofthehypothalamus. JNeuroendocrinol. 15(11):1075-83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01100.x.Article

- 9. Gong S, Miao YL, Jiao GZ, et al. 2015;Dynamicsandcorrelationofserumcortisolandcorticosteroneunderdifferentphysiologicalorstressfulconditionsinmice. PLoSOne. 10(2):e0117503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117503.Article

- 10. Harris RB, Mitchell TD, Simpson J, et al. 2002;Weightlossinratsexposedtorepeatedacuterestraintstressisindependentofenergyorleptinstatus. AmJPhysiolRegulIntegrCompPhysiol. 282(1):R77-88. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2002.282.1.R77.Article

- 11. Herdegen T, Leah JD. 1998;Inducible and constitutive transcription factors in the mammalian nervous system: Control of gene expression by Jun, Fos and Krox, and CREB/ATF proteins. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 28(3):370-490. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00018-6.ArticlePubMed

- 12. Hernández-Pérez OR, Hernández VS, Nava-Kopp AT, et al. 2019;Asynapticallyconnectedhypothalamicmagnocellularvasopressin-locuscoeruleusneuronalcircuitanditsplasticityinresponsetoemotionalandphysiologicalstress. FrontNeurosci. 20(13):196doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00196.

- 13. Kim D, Chung S, Lee SH, et al. 2017;Decreasedexpressionof5-HT1Ainthecircumvallatetastecellsinananimalmodelofdepression. ArchOralBiol. 20:42-47. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2017.01.005.Article

- 14. Kim DG, Lee S, Lim JS. 1999;Neonatal footshock stress alters adult behavior and hippocampal corticosteroid receptors. Neuroreport. 10(12):2551-2556. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908200-00021.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Lin X, Itoga CA, Taha S, et al. 2018;c-Fosmappingofbrainregionsactivatedbymulti-modalandelectricfootshockstress. NeurobiolStress. 7(8):92-102. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.02.001.Article

- 16. Mancuso C, Navarra P, Preziosi P. 2010;Roles of nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen sulfide in the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Neurochem. 113(3):563-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06606.x..ArticlePubMed

- 17. Marin MT, Cruz FC, Planeta CS. 2007;Chronic restraint or variable stresses differently affect the behavior, corticosterone secretion and body weight in rats. Physiol Behav. 90(1):29-35. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.08.021.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Masood A, Banerjee B, Vijayan VK, et al. 2003;Modulationofstress-inducedneurobehavioralchangesbynitricoxideinrats. EurJPharmacol. 90(1-2):135-9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02688-2.Article

- 19. McEwen BS. 2007;Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 87(3):873-904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Morilak DA, Barrera G, Echevarria DJ, et al. 2005;Roleofbrainnorepinephrineinthebehavioralresponsetostress. ProgNeuropsychopharmacolBiolPsychiatry. 29(8):1214-24. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.007.Article

- 21. Orlando GF, Wolf G, Engelmann M. 2008;Role of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the regulation of the neuroendocrine stress response in rodents: insights from mutant mice. Amino Acids. 35(1):17-27. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0630-0.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Itoi K, Sugimoto N. 2010;The brainstem noradrenergic systems in stress, anxiety and depression. J Neuroendocrinol. 22(5):355-61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.01988.x..ArticlePubMed

- 23. Sabban EL, Laukova M, Alaluf LG, et al. 2015;Locuscoeruleusresponsetosingle-prolongedstressandearlyinterventionwithintranasalneuropeptideY. JNeurochem. 135(5):975-86. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13347.ArticlePDF

- 24. Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. 2000;How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 21(1):55-89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Selye H. 1973;The evolution of the stress concept. American Scientist. 61(6):692-699.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Smagin GN, Howell LA, Redmann S Jr Jr, et al. 1999;Preventionofstress-inducedweightlossbythirdventricleCRFreceptorantagonist. AmJPhysiol. 276(5):R1461-8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1461.Article

- 27. Thakur T, Gulati K, Rai N, et al. 2017;Experimentalstudiesonpossibleregulatoryroleofnitricoxideonthedifferentialeffectsofchronicpredictableandunpredictablestressonadaptiveimmuneresponses. IntImmunopharmacol. 276:236-242. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.07.002.Article

- 28. Wang Y, Liberman MC. 2002;Restraint stress and protection from acoustic injury in mice. Hear Res. 276(1-2):96-102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00289-7.Article

- 29. Weinberg MS, Girotti M, Spencer RL. 2007;Restraint-induced fra-2 and c-fos expression in the rat forebrain: Relationship to stress duration. Neuroscience. 150(2):478-86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.013.ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader Cite

Cite